In a secular society, where fashion and toilets were a certain language in which the highest circles communicated, attire became a symbol of etiquette. Hence the appearance of milliners in the 18th century - the best dressmakers who sewed to individual orders, and then of Parisian dress shops.

Paris has always been the trendsetter of women's fashion. French tailors were invited by the crowned Elizabeth Petrovna, and her de facto successor, Catherine the Great, by decree of 1763, allowed foreigners to live and trade in Moscow with privileges. In Catherine’s time, French milliners and various fashion shops had already appeared in both capitals: the latter appeared under the names: “Au temple de gout” (Temple of Taste), “Musee de Nouveautes” (Museum of New Products), etc. At that time in Moscow famous milliner Vil, who sold fashionable "shelmovki" (sleeveless fur coats), caps, horns, magpies, "queen's rise" and La Greek, sterlet shoes, snails, women's skirt caftan, swinging chicken-form and furro-form, various bows, lace.

After the revolution of 1789, emigrants poured into Moscow. Among them was the famous Madame Marie-Rose Aubert-Chalmet. From the end of the 18th century, Madame had a store on Kuznetsky Most, and then in her own house in Glinishchevsky Lane near Tverskaya, where, among other things, she sold excellent hats at exorbitant prices, which is why Muscovites nicknamed her “over-scammer” - they even believe that the word swindler itself originated on her behalf. She had such a “arrival” that Glinishchevsky Lane was filled with carriages, and the store itself became a fashionable meeting center for the Moscow elite. Noble clients once saved the madam herself when her store was sealed for smuggling. The milliner's profile was very broad. They ordered a “dowry” from her for rich marriageable girls, and ball gowns - this is how Madame ended up on the pages of the epic “War and Peace”: it was to her that the old woman Akhrosimova was taken to dress the daughters of Count Rostov.

The milliner suffered a sad and unflattering fate. When Napoleon attacked Russia, two warring worlds collided on the Kuznetsky Bridge. Having become Napoleon's adviser, the experienced madam gave him valuable recommendations regarding politics in Russia, and together with Napoleon's army she left Moscow and died of typhus on the way.

Ober-Shalme was replaced by the even more famous milliner Sickler, in Moscow colloquialism Sikhlersha. In St. Petersburg she had a store near Gorokhovaya Street, and in Moscow - on Bolshaya Dmitrovka. She dressed the high society of Russia and her wives

celebrities.

One of Sickler’s regular clients was Natalie Pushkina, who loved to order toilets from her, and once gave a hat from Sickler as a gift to the wife of Pavel Nashchokin, Pushkin’s friend. From the poet’s letters it is known that the milliner more than once pestered him for his debts. They said that Pushkin paid Sickler for his wife’s toilets an amount almost greater than the fee for “The History of the Pugachev Rebellion,” and after Pushkin’s death, Sickler’s guardianship compensated Sickler for another 3 thousand of his debts.

High society ordered ballgowns from Sickler in the year when Nicholas I visited Moscow, for which the milliner earned 80 thousand a month. There were also incidents. Sometimes poor but gentle husbands spoiled their loved ones with great financial effort

the wives wore a dress from Sickler, but it turned out to be so luxurious that it was impossible to appear in it for the evening in the company of their circle, and for visits it was necessary to sew a new, simpler dress. M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin especially liked to be sarcastic about such husbands - his own wife ordered dresses for herself and her daughter only from Paris, and the wife’s “acquisitive appetites” greatly upset the satirist.

Sickler's successors were two Moscow milliners. The first was the “French artist” Madame Dubois, who had the best store on Bolshaya Dmitrovka with an elegant round hall, where there were always the best hats and not in display cases, but in cabinets - for connoisseurs.

Sickler's second successor from the 1850s was the famous Madame Minangua: her fame as the best milliner in Moscow did not fade until the revolution. Madame had luxury stores both on Bolshaya Dmitrovka and on Kuznetsky Most, which were dedicated exclusively to the latest Parisian fashions. Ladies' dresses, trousseaus, lingerie and elegantly decorated corsets were made here. It was the largest and most expensive company in old Moscow ordering capricious ladies' dresses, even at the time when they appeared in abundance

stores of ready-made European clothing.

The most important were the ball gowns, in which a woman appeared before the eyes of the capital's elite - according to etiquette, even in the most luxurious dress it was impossible to appear more than 3-4 times. The cheapest were girls' dresses: for the most pampered, it cost 80 silver rubles, light, with flounces, made of silk or gauze. The lady paid 200 silver rubles for the fabric alone for this toilet, and hundreds more rubles for the dress itself. An incredible luxury, which, contemporaries sighed, really should have been limited by some kind of law.

Ladies' outfits of the 18th and early 20th centuries.

Pictures enlarge when clicked

Moscow milliners of the 19th century.

From time immemorial, Odessa has also been known in Europe as a trendsetter; as Pushkin wrote about it, it was originally a European city. For this reason, local ladies flaunted here and amazed visiting provincials with the most elegant style and finest weaving with French straw hats from Madame Moulis or Victoria Olivier on Deribasovskaya in the Frapoli house, exquisite, latest fashion toilets from Adele Martin's stores on Italianskaya, now Pushkinskaya Street, Madame Palmer or

Suzanne Pomer. And Madame Lobadi, the owner of a chic salon on Richelieuskaya, periodically even invited special consultants from Paris itself, from whom customers could always “have all the news

Maud".

With the construction of an extensive shopping complex in 1842, which Odessa residents who visited the French capital soon began to call Palais Royal, the fashion store of Maria Ivanovna Stratz moved there. Opened in pre-Pushkin times and then existing for many years, this store became famous far beyond the borders of Odessa and for a long time had no similar store in almost the entire South. It's not surprising

it was, because there was literally everything that only the most capricious female soul could desire: ready-made outfits, woolen fabrics, Dutch linen, Lyon silks, French shawls, lace, gloves of unprecedented beauty, heavy velvet of all kinds of colors and the finest cambric, which seemed to flutter from one breath...

History of men's fashion. 20th century men's fashion

1900s in men's fashion

The last period of refined masculine elegance. St. Petersburg in the Silver Age was famous for its dandies. Russian fashionistas were guided by English fashion. The Prince of Wales, Queen Victoria's eldest son, later King Edward 7 was a style icon. It was he who first undid the button of his vest when he ate a hearty meal. He also introduced creases on trousers and rolled-up trouser legs into fashion.

A long coat, a frock coat and a bowler hat are in fashion.

1910s in men's fashion

Frock coats were replaced by cropped jackets without padded shoulders with high waists and elongated lapels. The men's suit has acquired a more elongated silhouette. Jazz is in fashion, and with it a jazz suit with trousers and a tightly buttoned jacket. The First World War popularized military uniforms. The military model - a trench coat (from the English word trench, "trench") for soldiers of the British army, supplied by Burberry - is becoming so popular that subsequently it continues to be worn in civilian life.

In St. Petersburg, the main refined dandy is Prince Felix Yusupov.

1920s in men's fashion

The Prince of Wales continued to be a fashion role model. He introduced into fashion shortened wide golf pants “plus fours”, with which long woolen socks were worn. During this period, Scottish Fair Isle sweaters, Panama hats, narrow Windsor knot ties, two-button jackets, pocket squares, brown suede shoes and gingham caps are worn. By the way, the pattern on men's suit fabrics “Prince of Wales” is named after Edward 7, who loved informal checkered suits.

In Russia this is a time of war communism and civil war. After the 1917 revolution, the dandies of the Silver Age disappeared. They are being replaced by avant-garde artists of a new formation.

The fashionista of that time was Vladimir Mayakovsky.

Real dudes appeared in the era of the New Economic Policy. They wore striped trousers, bow ties, floppy hats and boaters, and tried to look like Jazz Age Americans.

1930s men's fashion

Fashionistas imitate glamorous Hollywood stars. Popular hobbies include aviation, cars and sports. A fit, athletic physique is in fashion.

Suits took on a more masculine look, the shoulder line increased, the chest expanded, and the jacket began to fit closer to the hips. Sports style items, jeans and knitwear appear in the men's wardrobe. They wore caps and leather helmets on their heads. In the 30s, the so-called “captains” hats with lacquered visors were popular. Brown and khaki dominate the color scheme of clothing.

During the war years, Russian dandies and dandies fell in love with trophy fashion. Things brought from Germany and other countries became fashionable goods for those who would later be called dudes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

1940s in men's fashion

The key image of a man during the Second World War is masculine and in military uniform. Common items were short coats and short jackets with patch pockets.

In the first period of the post-war period, unusual suits called zoot suits appeared in America, which consisted of a long double-breasted jacket to the knees with wide lapels and baggy trousers, tapered at the bottom, and a wide-brimmed hat was worn with the suit.

In Soviet fashion of the post-war period, compared to the 1930s, the actual silhouette became wider, things seemed to be a little big. An important men's business accessory was the felt hat. They wear double-breasted jackets, wide trousers and long coats. Dark tones predominated. Light and striped suits were considered especially chic. Even after the war, military uniforms remained common clothing in civilian life; the image of a man in uniform was incredibly popular. Among other things, leather coats have come into fashion.

Since 1947, styling began to captivate large circles of Soviet youth.

|

|

|

|

1950s in men's fashion

The post-war world was changing rapidly, and fashion was changing with it. In England, in the early 1950s, a style called “Teddy Boys” appeared. This style is a variation of the style of Edward 7 (Edwardian era), hence the name (in English, Teddy is an abbreviation for the full name Edward). They wore tapered trousers with cuffs, a straight-cut jacket with a velvet or moleskin lapel, narrow ties and platform boots (creepers). The bangs were styled into a curl.

In 1955, rock and roll entered the lives of British youth, reflected in clothing in the form of silk suits, bell-bottom trousers, open collars and medallions.

In 1958, Italian influence came into English fashion. Fashion includes short square jackets, tapered trousers, white shirts with thin ties and vests with a scarf peeking out of the chest pocket of the vest. The boots acquired a pointed shape (Winkle picker).

1960s in men's fashion

Significant changes are taking place in the world of men's fashion: the industry of mass production of ready-to-wear suits is being launched. The gray suit becomes the uniform of office workers. A loose long jacket, button-down collar shirts, a skinny tie, Oxford shoes, a black wool coat and a felt hat are in fashion.

|

In 1967, among young people there was a revival of the teddy boy style, which received the new name rockabilly, a new version of the style was ennobled by the trend of glam rock. Costumes acquired garish colors.

1970s in men's fashion

Unlike the 1960s, in the 70s there was no single direction in fashion; there were different trends. Fashion as a way of self-expression. Trends were shaped by street fashion. Among the youth, the hippie movement: long hair, bell-bottom jeans, colorful shirts, baubles, neck pendants and beads as accessories.

Clothes are becoming more versatile and practical. There are a variety of styles and their mixtures in use. Turtlenecks became a cult item of clothing in the 1970s. Noodle turtlenecks are popular in the Soviet Union.

|

|

1980s in men's fashion

A new generation of businessmen and luxury consumers, called yuppies, has emerged.

Italian fashion has become relevant, making tanning, black glasses and brown shoes popular. The men's wardrobe ceased to be universal and was strictly divided into business, evening and casual. Corporations are introducing a “working Friday” dress code.

In the Soviet Union, banana and boiled jeans were at the peak of popularity. Black marketeers flourished; branded clothing brought from abroad was considered a sign of wealth and style.

1990s in men's fashion

In the West, minimalism, simplicity and practicality have become the main fashion trends as opposed to the rampant consumption of the 80s. Men's business clothing has become looser and simpler. Sports are popular and sportswear with logos of famous brands is becoming everyday wear.

The grunge style is common among young people: large, baggy clothes in dark tones. The variety of subcultures: rap, hip-hop, rock determines the appearance of teenagers.

Unisex style is popular. Casual clothing becomes the basis of a man's wardrobe.

In Russia, men's business fashion is dominated by the notorious crimson jacket - the personification of success and prosperity.

In the late 90s, the widespread use of information technology leads to the rapid spread of fashion trends in the world.

2000s in men's fashion

This is the era of metrosexuals. The cult of a beautiful body becomes the main idea of fashion. A sleek appearance and a pronounced interest in fashion trends are in fashion.

|

|

Based on sources:

Style Bible: the wardrobe of a successful man / N. Naydenskaya, I. Trubetskova.

D/f “Blow of the Century. Life of a dandy"

Join our group

Clothes of townspeople (1917-1922)

The First World War, the revolutionary coup and the Civil War changed the appearance of Russian citizens. The iconic symbolism of the costume began to appear more clearly. This was a time when solidarity or opposition was expressed with the help of a suit or its individual parts; it was used as a screen behind which one could temporarily hide one’s true attitude to the events taking place. “In Moscow they gave out oats using ration cards. Never before has the capital of the republic experienced such a difficult time as in the winter of the twentieth year.” It was “the era of endless hungry queues, “tails” in front of empty “food distributors”, an epic era of rotten frozen carrion, moldy bread crusts and inedible surrogates.

“They don’t sell any firewood. There is nothing to drown the Dutch with. In the rooms there are iron stoves - potbelly stoves. From them there are samovar pipes under the ceiling. One into the other, one into the other, and right into the holes in the boards with which the windows are sealed; jars are hung at the joints of the pipes so that the resin does not drip.” . And yet, many still continued to follow fashion, although this was limited only by the silhouette of the suit or some details, for example, the design of the collar, the shape of the hat, and the height of the heel. The silhouette of women's clothing was on the path to simplification. It can be assumed that this trend was influenced not only by Parisian fashion (the Gabrielle Chanel clothing house, opened in 1916, promoted “robes de chemise” - simple forms of dress, not complicated by cut), but also by economic reasons. “Magazine for housewives” in 1916. wrote: “... there is almost no fabric in warehouses or stores, there are no trims, there is not even thread to sew a dress or coat.” “...for a spool of thread (such a spool... small) in the Samara province they give two pounds of flour... two pounds for such a small spool...” we learn from the “Diaries” of K. I. Chukovsky.

During this period, the price of cloth rose from 3 rubles. 64 k. (average price 1893) up to 80,890 rubles. in 1918 . Then the inflationary spiral unwinded more and more. Information from the “Diary of a Muscovite”, in which the author N.P. Okunev daily recorded all everyday events, significant and trivial, is invaluable. “I ordered a pair of jackets for myself, the price was 300 rubles, I thought I was crazy, but they tell me that others pay 4,008,500 rubles for suits. A complete bacchanalia of life!”

This economic situation did not contribute to the development of a fashionable suit, but it gave rise to very interesting forms of clothing. If in M. Chudakova’s “Biography of M. Bulgakov” we read about 1919: “in March, a colleague of our hero, a Kiev doctor, wrote in his diary: “... no practice, no money either. And life here is becoming more expensive every day. Black bread already costs 4 rubles. 50 k. per pound, white - 6.50, etc. And most importantly - on a hunger strike. Black bread – 12815 rub. per pound. And there is no end in sight.” That was already in 1921. in a letter to his mother, Mikhail Bulgakov writes: “In Moscow they only count in hundreds of thousands and millions. Black bread 4600 rub. per pound, white 14,000. And the price goes up and up! The stores are full of goods, but what can you buy? The theaters are full, but yesterday, when I passed by the Bolshoi on business (I can no longer imagine how you could go without business!), the dealers were selling tickets for 75, 100, 150 thousand rubles! Moscow has everything: shoes, fabrics, meat, caviar, canned food, delicacies - everything! Cafes are opening and growing like mushrooms. And everywhere there are hundreds, hundreds! Hundreds!! A wave of speculators is buzzing."

The memories of I. Odoevtseva are colored with irony. “He (O. Mandelstam, editor's note) had never seen women in a man's suit. In those days this was completely unthinkable. Only many years later, Marlene Dietrich introduced the fashion for men's suits. But it turns out that the first woman in pants was not her, but Mandelstam’s wife. It was not Marlene Dietrich, but Nadezhda Mandelstam who revolutionized the women's wardrobe. But, unlike Marlene Dietrich, this did not bring her fame. Her bold innovation was not appreciated either by Moscow or even by her own husband."

This is how M. Tsvetaeva described her “outfit” at a poetry evening at the Polytechnic Museum in 1921: “Not mentioning yourself, having gone through approximately everyone, would be hypocrisy. So, on that day I was revealed to “Rome and the world” in a green dress, like a cassock, which cannot be called (a paraphrase of the best times of a coat), honestly (that is, tightly) tied not even with an officer’s, but with a cadet’s belt, the 18th Peterhof School of Ensigns. . Over the shoulder is also an officer’s bag (brown, leather, for field binoculars or cigarettes), which would be considered treason to take off and was removed only on the third day after arriving (1922) in Berlin... Legs in gray felt boots, although not men’s, on the leg, surrounded by lacquered boats they looked like pillars of an elephant. The whole toilet, precisely because of its monstrosity, removed from me any suspicion of deliberateness.” The notes of contemporaries are surprisingly frank. “And so I jump up, still in the complete darkness of the winter night, throw on an old fur coat and a scarf (after all, it’s not good to stand in line in a hat, let the servants think that they are their brother, otherwise they will mock the lady).” Due to the change in the position of women that has occurred since the beginning of the war, a number of forms of men's clothing are transferred to women's. In 191681917 These are men's type vests, in 1918-1920 leather jackets, which passed into everyday life from decommissioned military uniforms. (In 1916, scooter riders in the Russian army wore leather jackets). Due to the lack of information, the severance of traditional ties with Europe, the difficult economic situation and at the same time the preservation of clothing of old forms, the costume of many women presented a rather eclectic picture. (This is evidenced by drawings, photographs, and sculpture of those years). For example, a female police officer was dressed like this: a leather jacket, a uniform blue beret, a brown plush skirt and lace-up boots with a cloth top. The non-serving ladies looked no less exotic. In the “Diaries” of K. I. Chukovsky we read: “Yesterday I was in the House of Writers: everyone’s clothes were wrinkled, saggy, it was clear that people slept without undressing, covering themselves with coats. Women are chewed up. It’s as if someone chewed them and spat them out.” This feeling of bruising and fraying still arises when looking at photographs of that time. Old forms of clothing are preserved everywhere. Moreover, in the working environment they continue to sew dresses in the fashion of the beginning of the century, and in provincial towns on the national outskirts, clothing is influenced by the traditions of the national costume. In 1917 the silhouette of a woman's dress still retains the outlines inherent in the previous period, but the waist becomes much looser, the skirt is straighter and slightly longer (up to 12 cm above the ankle). The silhouette resembles an elongated oval. At the bottom, the skirt narrows to 1.5-1.7 m. After 1917 Two silhouettes coexist in parallel: widened at the bottom and a “tube” so-called “rob de chemise” shirt dress. Shirt dresses appeared in Russia before (S. Diaghilev’s memories of N. Goncharova date back to 1914): “But the most curious thing is that they imitate her not only as an artist, but also in appearance. It was she who introduced into fashion the shirt-dress, black and white, blue and red. But that's nothing yet. She drew flowers on her face. And soon the nobility and bohemians rode out on sleighs with horses, houses, elephants on their cheeks, on their necks, on their foreheads.”

Silhouette of a dress 1920-1921. a straight bodice, the waist is lowered to the level of the hips, the skirt, easily draped in folds, 8-12 cm long above the ankle, is already significantly close to the fashion of subsequent years. But one could often see a lady in a dress made from curtain fabric. And although this issue seems controversial to contemporaries, enough examples can be found in the literature. So from A.N. Tolstoy: “Then the war ended. Olga Vyacheslavovna bought a skirt made of green plush curtain at the market and went to serve in various institutions.” Or from Nina Berberova: “I was left without work; I had felt boots from a carpet, a dress from a tablecloth, a fur coat from my mother’s rotunda, a hat from a sofa cushion embroidered with gold.” It is difficult to say whether this was an artistic exaggeration or reality. Fabrics produced in the country in the period 1920-1923. “they were distinguished by their simplicity and were printed according to the least labor-intensive old models.” But there were apparently few of them, so dresses made from curtains became a ubiquitous phenomenon. Tatyana Nikolaevna Lappa recalls this in “The Biography of M. Bulgakov”: “I went in my only black crepe de Chine dress with panne velvet: I altered it from my previous summer coat and skirt.” Chests were opened, and grandmother's outfits were brought to light: dresses with puffed sleeves, with trains. Let us recall from M. Tsvetaeva: “I dive under my feet into the blackness of a huge wardrobe and immediately find myself seventy years old and seven years ago; not at seventy-seven years old, but at 70 and 7. I feel with the dreamlike infallible knowledge of something that has long ago and obviously from the weight fallen, swollen, settled, spilled into a whole pewter puddle of silk, and I fill myself with it up to my shoulders.” And further: “And a new dive to the black bottom, and again the hand is in a puddle, but no longer of tin, but of mercury with water running away, playing from under the hands, not collected into a handful, scattering, scattering from under the rowing fingers, because if the first it sank from the heaviness, the second one flew off from the lightness: from a hanger as if from a branch. And behind the first, settled, brown, faye, great-grandmother Countess Ledochovskaya great-grandmother Countess Ledochovskaya unstitched, her daughter my grandmother Maria Lukinichnaya Bernatskaya unstitched, her daughter my mother Maria Alexandrovna Main unstitched, sewn by the great-granddaughter of the first Marina in our Polish family by me, mine, seven years back, as a girl, but in the cut of my great-grandmother: the bodice is like a cape, and the skirt is like the sea...” Contemporaries recall that “the old dresses of mothers and grandmothers were altered, decorations and lace were removed from them “bourgeois burp.” Struggling against any manifestation of “bourgeoisism,” the blueshirts sang: “Our charter is strict: no rings, no earrings. Our ethics, down with cosmetics”... People were stigmatized for jewelry and Komsomol membership cards were taken away. This did not apply to the fashions of the revived bourgeois ladies during the NEP, since these were hostile elements." In magazines of 1917-1918. Recommendations appear on how to make a new one out of an old dress, how to sew a hat, even how to make shoes. In the 1918-1920s, a lot of homemade shoes with wooden, cardboard, and rope soles appeared in everyday life. V.G. Korolenko in a letter to A.V. Lunacharsky wrote: “...look at what your Red Army soldiers and your serving intelligentsia wear: you will often see a Red Army soldier in bast shoes, and serving intelligentsia in poorly made wooden sandals. It’s reminiscent of classical antiquity, but now it’s very inconvenient for winter.” Fashion at this time offers two-inch heels (about 9 cm high). By the early 20s, the heel not only rose, but also tapered downward. Contemporaries testify: “In 1922-1923. Coarse military boots with windings are disappearing. The army puts on its boots." The silhouette of military clothing is also transformed. After 1917 coats lengthen again, the waist gradually drops 5-7 cm below natural. Fashion 1917 as if referring to folk costume. The magazine “Ladies' World” (No. 2; 1917) writes that the fashion is “imitation in the cut of warm ladies’ coats of caftans and fur coats from various provinces. The cut of Ekaterinoslav’s “woman’s” outfits - wide fur coats at the bottom, with cut-off waists and huge turn-down collars falling on the shoulders - seems very fashionable, straight out of a Parisian magazine.” In fact, the simplification of the form led to traditionally simple forms of folk costume.

The color scheme of the clothes was dominated by natural brown tones. In 1918 “a fashionable color is dark earthy, both plain and melange”

, “camel” color combined with black. The huge wide-brimmed hats of the pre-war era are a thing of the past, however, many styles of hats have remained in use for a long time. A girl in a hat, for example, can be seen in the photo of the parade of General Education troops in 1918. on Red Square and among Komsomol members organizing educational programs in the Rostov region. The “first ladies” of the state also wore hats - N.K. Krupskaya, M.I. Ulyanova, A.M. Kollontai. True, we are talking about small hats with rather narrow brims, small in size, decorated, as a rule, only with a bow, but their ubiquity and widest distribution, both in the provinces and in the capital, is beyond doubt.

In 1918 Boas and gorgets are going out of fashion; to replace them, magazines offer scarves with edges trimmed with fur, lace, and tassels. These scarves were worn both around the neck and on the hat. Knitted scarves were most often used in everyday life.

In men's clothing, the most active period in politics and social reorganization did not give any new forms, but only served as an impetus for the destruction of the traditions of wearing it. The men's suit retains the shapes of previous years, with only minor changes in details. In 1918-1920 Only turn-down collars of shirts and blouses remain in everyday use; stand-up collars are not gaining further popularity. Tie knot after 1920 stretches out, becomes narrow and approaches a rectangle as much as possible, and the tie itself is narrower and longer. Their colors are faded and dull. The norm is an altered men's suit. In A. Mariengof’s “Memoirs” we read: “Shershenevich is wearing a chic light gray jacket with a large check. But the treacherous left pocket... is on the right side, since the jacket is upside down. Almost all dandies of that era had their top pockets on the right side.” Men's clothing is becoming as militarized as possible and at the same time, it is losing the traditionally established rules of color matching of shoes to trousers, and both to the jacket. A French jacket in combination with some kind of trousers is becoming the most popular clothing for men. “He was wearing a paramilitary suit - an English jacket, checkered, with leather on the backside, riding breeches and black boots.” “After Brest, many demobilized people appeared at the stations. Soldiers' greatcoats "came into fashion" - they hung in almost every hallway, exuding the smell of shag, station burning and rotten earth. In the evenings, when going out, we put on overcoats - it was safer in them.” Knitwear is widely used in everyday life, apparently due to the relative ease of production. From Kataev: “Vanya was dressed in a black tunic, mustard riding pants and huge, above-the-knee, clumsy cowhide boots that made him look like a puss in boots. On top of the tunic, around the neck, was a thick collar of a market paper sweater." Leather jackets were not only very popular, but were also a mandatory distinction for commanders, commissars and political workers of the Red Army, as well as employees of technical troops. True, contemporaries deny their mass distribution. They continued to wear the uniforms of various departments. And if in 1914-1917. The uniform of officials was not observed so strictly, but since 1918. and completely ceases to correspond to the position held and remains in everyday use as usual clothing. After the abolition of old ranks and titles in January 1918. military uniforms of the tsarist army began to be worn with bone or fabric-covered buttons (instead of buttons with a coat of arms). “It was officially announced that all distinctions, including shoulder straps, would be abolished. We were forced to remove them, and instead of buttons with eagles, sew on civilian bone ones or cover the old metal ones with fabric.” Contemporaries recall that “... in the 20s, a campaign began against student caps, and their owners were persecuted for their bourgeois way of thinking.”

Eclecticism was also inherent in the men's suit. This is what I. Bunin wrote about the clothes of the Red Army soldiers: “They are dressed in some kind of prefabricated rags. Sometimes a uniform from the 70s, sometimes, out of the blue, red leggings and at the same time an infantry overcoat and a huge Old Testament saber.” But representatives of another class were dressed no less extravagantly. In the book “Biography of M. Bulgakov” we read: “On some day of this winter, in house No. 13 on Andreevsky Spusk, an episode occurred that was preserved in Tatyana Nikolaevna’s memory. One time the bluebacks came. They are shod in ladies' boots, and the boots have spurs. And everyone is perfumed with Coeur de Jeannette - a fashionable perfume."

The appearance of the crowd and individuals was lumpen. Let's turn again to the literature. From Bunin: “In general, you often see students: in a hurry somewhere, all torn to pieces, in a dirty nightgown under an old open overcoat, a faded cap on his shaggy head, knocked-down shoes on his feet, a rifle hanging on a rope with the muzzle down on his shoulder...

However, the devil knows whether he is really a student.” And here’s what the crowd looked like in M. Bulgakov’s description: “Among them were teenagers in khaki shirts, there were girls without hats, some in a white sailor blouse, some in a colorful sweater. There were sandals on bare feet, black worn-out shoes, young men in blunt-toed boots.” Vl. Khodasevich recalled that before the war, individual literary associations could afford something like a uniform. “To get into this sanctuary, I had to sew black trousers and an ambiguous jacket to go with them: not a gymnasium jacket, because it’s black, but not a student’s jacket either, because it has silver buttons. In this outfit I must have looked like a telegraph operator, but everything was redeemed by the opportunity to finally attend Tuesday: on Tuesdays literary interviews took place in the circle.” Literary figures and actors acquire a unique, even exotic appearance. But this was not so much the outrageousness of the futurists’ clothes (Mayakovsky’s notorious yellow jacket), but rather the simple absence of clothing as such and the random sources of its acquisition. M. Chagall recalled: “I wore wide trousers and a yellow duster (a gift from the Americans, who out of mercy sent us used clothes)…”. M. Bulgakov, according to Tatyana Nikolaevna’s memoirs, at that time wore a fur coat “... in the form of a rotunda, such as old men of clergy wore. On raccoon fur, and the collar turned outward with the fur. The top was blue ribbed. It was long and without fasteners - it really wrapped up and that’s all. It was probably my father's fur coat. Maybe his mother sent it to him from Kyiv with someone, or maybe he brought it himself in 1923...” The poet Nikolai Ushakov wrote in 1929. in his memoirs: “In 1918-1919, Kyiv became a literary center; Ehrenburg walked in those days in a coat that dragged along the sidewalks and in a gigantic wide-brimmed hat...”

Based on all these materials - memories, photographs - we can conclude that men's clothing of this period was extremely eclectic in nature and, in the absence of stylistic unity, was based on the personal tastes and capabilities of its owner. From 1922-1923 Domestic fashion magazines are starting to appear. But, although at this time such masters as N.P. Lamanova, L.S. Popova, V.E. Tatlin were making attempts to create new clothes that corresponded to the spirit of the time, and in particular overalls, their experiments were only sketchy in nature.

The last century was the time of crinolines, bustles, “polonaise”, dolman, abundant ruffles and frills of all kinds. The century that follows, the height of the Belle Epoque, is characterized by simplicity and common sense, and although the details are still carefully worked out, the elaborate decoration of the dress and unnatural lines gradually fade into the background. This desire for simplicity became even stronger with the outbreak of the First World War, which clearly proclaimed the two main principles of women's dress - freedom and ease of wearing.

The Belle Epoque - a time of luxury

In the 1900s, if you were a sophisticated young English lady belonging to the elite of society, you were supposed to make a pilgrimage to Paris twice a year along with other similar women from New York or St. Petersburg.

In March and September, groups of women could be seen visiting studios on rue Halevy, la rue Auber, rue de la Paix, rue Taitbout and Place Vendôme.

In these often cramped shops, with seamstresses working feverishly in the back rooms, they met with their personal salesperson, who helped them choose their wardrobe for the next season.

This woman was their ally and knew all the darkest secrets of their lives, both personal and financial! The survival of these early fashion houses depended entirely on their powerful clients, and knowing their little secrets helped them in this!

Armed with copies of Les Modes, they looked through the latest creations of great couturiers such as Poiret, Worth, the Callot sisters, Jeanne Paquin, Madeleine Chéruy and others to come up with a wardrobe that would outshine the wardrobes of not only friends, but also enemies!

Decades passed, and these terrible magazine images of static women, where every seam and every stitch was visible, were supplanted by the freer and more fluid Art Nouveau style, which used new photographic methods of depiction.

Together with the seller, the women chose a wardrobe for the next six months: underwear, loungewear, dresses for walking, options for alternating clothes, suits for traveling by train or in the car, evening dresses for leisure time, outfits for special occasions such as Ascot, wedding, visit to the theater. The list goes on and on, it all depends on the size of your wallet!

Edwardian lady's wardrobe (1901-1910)

Let's start with the body wardrobe. It consisted of several pieces of underwear - day and nightgowns, pantaloons, knee socks and petticoats.

Women began their day by choosing a combination, then put on an s-shaped corset, over which came a bodice cover.

Next came the daytime ensemble. These were usually formal morning clothes that could be worn when meeting friends or while shopping. As a rule, it consisted of a neat blouse and a wedge-shaped skirt; in cool weather, a jacket was worn on top.

Returning to lunch, it was necessary to quickly change into day clothes. In the summer it was always some kind of colorful clothes in pastel colors.

By 5 o'clock in the evening it was possible, which was done with relief, to take off the corset and put on a tea outfit to relax and receive friends.

By 8 o'clock in the evening the woman was again pulled into the corset. Sometimes the underwear was changed for fresh ones. After this came the turn of an evening dress for home or, if necessary, for going out.

By 1910, such dresses began to undergo changes under the influence of the works of Paul Poiret, whose satin and silk dresses, inspired by oriental motifs, became very popular among the elite. A big hit in London in 1910 was ladies' trousers as fancy dress for evening wear!

During the day it was also necessary to change stockings at least twice a day - cotton ones for wearing during the day - in the evening they were changed to beautiful embroidered silk stockings. It wasn't easy being an Edwardian woman!

Edwardian silhouette – myths and reality.

1900 - 1910

Before 1900 every high society lady - with the help of her maid - was forced to tighten herself daily into tight corsets that made it difficult to breathe, as her mother and grandmother did. It was very painful for the woman! Certainly, the sale of smelling salts was very profitable in that era.

Before 1900 every high society lady - with the help of her maid - was forced to tighten herself daily into tight corsets that made it difficult to breathe, as her mother and grandmother did. It was very painful for the woman! Certainly, the sale of smelling salts was very profitable in that era.

The purpose of the corset [if the illustrations are to be believed] was to push the upper body forward, like a dove, and to push the hips back. However, Marion McNeely, comparing the illustrations with photographs of women in the 1900s. in their daily lives, suggested in Foundations Revealed that the real purpose of s-shaped corsets was a conspicuously upright posture, designed to accentuate the curves of the hips and chest by pushing back the shoulders, causing the chest to rise and the hips to round out.

My opinion on this issue is that there is a tendency, as in modern fashion illustrations, to overemphasize the lines. Comparing the above picture of the Lucille fashion house from 1905 with Edward Sambourne's beautiful natural photograph of a young woman in London proves the fact that women did not tighten their corsets too much!

It was most likely an idealized version of the Edwardian woman of the time, popularized by Charles Dana Gibson's illustrations and postcards of Gibson's girlfriend Camilla Clifford, leaving us with a highly exaggerated impression of the female form of the Edwardian era.

Fashion in dresses – 1900 – 1909

Women began to wear jackets in a strict style, long skirts [the hem was slightly raised], and high-heeled ankle boots.

The silhouette gradually began to change from an s-shape in 1901 to an empire line by 1910. The typical colors for everyday clothing for women in the Edwardian period were a combination of two colors: a light top and a dark bottom. The material is linen [for the poor], cotton [for the middle class], and silk and quality cotton [for the upper class].

In terms of details, during the Belle Epoque, lace frills signaled a woman's social status. Numerous ruffles on the shoulders and bodice, as well as appliqués on skirts and dresses.

Despite the ban on wearing corsets, women, especially those from the new middle class, began to experience greater social freedom. It has become quite normal for women to travel abroad on bicycles - to the Alps or Italy, for example, as beautifully captured in the melodramatic film A Room with a View, based on the book by E.M. Forster, which he published in 1908.

Popular casual clothing consisted of a white or light cotton blouse with a high collar and a dark, wedge-shaped skirt that started under the chest and flowed down to the ankles. Some skirts were also sewn into the corsetry from the waist to the area under the bust. This style: a simple sports blouse and skirt, first appeared in the late 1890s.

Often there was only one seam on the skirts, as a result of which even the most hopeless figures acquired a pleasant slimness!

Skirts and dresses were sewn to the floor, but in such a way that it was convenient for women to climb into the carts. By 1910, the hem became shorter and ended slightly above the ankle. Initially, the silhouette of blouses featured voluminous shoulders, but by 1914 they were significantly reduced in volume, which, in turn, led to greater roundness of the hips.

By 1905, with the growing popularity of automobiles, fashion-conscious women began to wear a manteau or semi-long coat in the fall and winter. These coats were very fashionable and went from the shoulder to below the waist, which was approximately 15 inches long. In such an outfit, and even in a new short skirt that did not even reach her ankles, the woman looked very bold! If it was damp or snowing outside, you could put a duster on top to protect your clothes from dirt.

The afternoon dress, although made in a variety of pastel shades and with extensive embroidery, was still quite conservative in the 1900s, as it was worn to attend formal dinners, meetings and conservative women's gatherings - here the dress code was influenced by women with Victorian views on life!

The tea dresses, which women usually wore by 5 pm if they were at home, were excellent: they were usually made of cotton, white and very comfortable. This was the only time for an Edwardian woman when she could take off her corset and breathe normally! Women often met and entertained friends in a tea dress, because they could afford to be extremely informal!

In Edwardian Britain, women were given the opportunity to show off their finest clothes from Paris during the London season, which ran from February to July. From Covent Garden, royal receptions and private balls and concerts, to the races at Ascot, society's elite showed off their latest, greatest and worst.

Evening dresses in the Edwardian period were frilly and provocative, with low necklines that openly showed off the woman's breasts and her jewelry! Evening dresses in the 1900s sewn from luxurious material. By 1910, women began to tire of large evening dresses, especially the French, who decided to abandon trains on their dresses and switched to the Empire style from Poiret, inspired by the Russian Seasons.

In 1909, when the Edwardian period was already coming to an end, a strange fashion arose for tight skirts with an interception below the knee, whose advent is also attributed to Paul Poiret.

Such narrow skirts tightly pulled the woman’s knees, making it difficult to move. Combined with the increasingly popular wide-brimmed hats (in some cases measuring up to 3 feet), made popular by Lucille, Poiret's main American competitor, it began to seem that fashion had gone beyond the bounds of reason by 1910.

Hairstyles and ladies' hats in the Edwardian period 1900 - 1918.

Fashion magazines of that time began to pay great attention to hairstyles. The most popular back then were curls curled with curling irons in the Pompadour style, as this was one of the fastest ways to style hair. In 1911, the 10-minute Pompadour hairstyle becomes the most popular!

These hairstyles held up well to surprisingly large hats that dwarfed the hairstyles they were pinned to.

By 1910, Pompadour hairstyles gradually gave way to Low Pompadour, which in turn evolved into simple low buns with the onset of World War I.

To take advantage of this hairstyle, hats began to be worn lower, right on the bun, and the wide brims and bright feathers of previous years were gone. Wartime regulations discouraged such things.

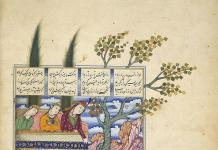

“Russian Seasons” 1909 – Wind of Change

By 1900, Paris was the fashion capital of the world, with Worth, Callot Soeurs, Doucet and Paquin among the leading names. Haute couture, or haute couture, was the name given to an enterprise that used the most expensive fabrics to sell them to the influential elite of Paris, London and New York. However, the style remained the same - Empire lines and Directory style - high waists and straight lines, pastel colors such as greenish Nile water, pale pink and sky blue, reminiscent of the tea dresses and evening dresses of the elite of society.

It's time for change. This was preceded by the following events: the influence of the Art Deco style, which arose from the modernist movement; the advent of the Russian Seasons, first held in 1906 in the form of an exhibition organized by their founder Sergei Diaghilev, the phenomenal performances of the Russian Imperial Ballet in 1909 with their luxurious costumes inspired by the East and created by Leon Bakst.

The dancer Nijinsky's bloomers caused great surprise among women, and the master of opportunism Paul Poiret, considering their potential, created the harem skirt, which for a time became very popular among young people from the British upper class. Poiret, perhaps influenced by Bakst's 1906 illustrations, felt the need to create more expressive illustrations for his creations, as a result of which he hired the then unknown Art Nouveau illustrator Paul Iribeau to illustrate his work "Paul Poiret's Dresses" in 1908. It is impossible to overestimate the influence that this work had on the emergence of fashion and art. After this, these two great masters worked together for two decades.

The emergence of modern fashion – 1912 – 1919

By 1912, the silhouette acquired a more natural outline. Women began to wear long, straight corsets as the basis for tight-fitting daytime outfits.

Oddly enough, the brief return to the past in 1914 was simply nostalgia: most fashion houses, including the Poiret fashion house, presented temporary stylish solutions with bustles, hoops and garters. However, the desire for change could no longer be stopped, and by 1915, in the midst of the raging bloody war in Europe, the Callot sisters introduced a completely new silhouette - an unringed women's chemise over a straight base.

Another interesting innovation during the early war years was the introduction of the color-matched blouse, the first step towards a casual style that was destined to become a staple of women's clothing.

Coco Chanel adored women's chemises or shirt dresses and, thanks to her love of the popular American jacket or sailor blouse [a loose-fitting blouse tied with a belt], she adapted the jumpers worn by sailors in the popular seaside town of Deauville (where she opened a new store), and created a women's cardigan with statement everyday straps and pockets that foreshadowed the 1920 fashion look 5 years before it became the norm.

Like Chanel, another designer, Jeanne Lanvin, who specialized in clothing for young women during this period, also liked the simplicity of the chemise and began creating summer dresses for her clients that heralded a shift away from restrictive dresses.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 did not put an end to the international showing of Parisian collections. But despite the attempts of American Vogue editor Edna Woolman Chase to organize charity events to help the French fashion industry, Paris was justifiably concerned that America, being a competitor to Paris, intended to benefit from the situation in one way or another. If you are lucky enough to have fashionable French vintage periodicals of the time, such as Les Modes and La Petit Echo de la Mode, note that they rarely contain any mention of the war.

However, the war was going on everywhere, and women's dresses, as in the 1940s, of necessity, became more military.

Clothing became reasonable - jackets of strict lines, even warm overcoats and trousers acquired special feminine shapes if they were worn by women who helped in the war. In Britain, women joined volunteer medical units and served in the SV nursing service. In the USA there was a reserve of female auxiliary personnel of the MP, as well as special women's battalions.

Such military groups were intended for upper-class women, while working-class women in various countries, especially Germany, worked in military factories. As a result of such a shake-up of social classes, when poor and rich, men and women were all together, the phenomenon of emancipation in women's dress grew like never before.

1915 - 1919 – New silhouette.

It was the time of the Art Nouveau figure

Now the emphasis in women's underwear was not on giving shape to the female figure, but on supporting it. The traditional corset has evolved into a bra that is now essential for the more physically active woman. The first modern bra appeared thanks to Mary Phelps Jacob; she patented this creation in 1914.

The traditional bodice has been replaced by a fashion for a high waist, tied with a beautiful wide scarf belt. Fabrics such as natural silk, linen, cotton and wool were used, and artificial silk was also used - twill, gabardine (wool), organza (silk) and chiffon (cotton, silk or viscose). Thanks to young designers such as Coco Chanel, materials such as jersey and denim began to become part of life.

In 1910 a horizontal view of dress design appeared. As an alternative, vertical capes were used, such as Poiret's popular kimono jackets, worn over a clean jacket and skirt set. The hem of casual clothing was located slightly above the ankle; The traditional floor length of an evening dress began to rise slightly in 1910.

By 1915, with the advent of the flared skirt (also known as the military crinoline), the shortening of clothing length, and therefore the appearance of now visible shoes, a new silhouette began to emerge. Lace-up shoes with heels became a nice addition to the models for the winter - beige and white colors joined the usual black and brown colors! With the development of hostilities, evening dresses, as well as clothes for tea, began to disappear from the collections.

Annette Kellerman - the swimsuit revolution

Swimwear designs of the Edwardian period led to the overthrow of social mores when women began to show off their legs on the beach, albeit clad in stockings.

Aside from the Australians, especially Australian swimmer Annette Kellerman, who in some ways revolutionized the swimsuit, swimwear changed gradually from 1900 to 1920.

Kellerman caused quite a stir when, upon arriving in the US, she appeared on the beach in a tight swimsuit, which resulted in her being arrested in Massachusetts for indecent exposure. Her trial marked a turning point in the history of the swimsuit, and also helped eliminate the outdated norms that led to her incarceration. She created the look for the Max Sennett swimsuit babes, as well as the standards for the sexy Jantzen swimsuits that came later.

The Birth of the Charleston Dress

It's difficult to pinpoint exactly when the low-waisted tomboy dress style that became the norm by 1920 emerged. The mother-daughter image created by Jeanne Lanvin in 1914 is eye-catching here.

Take a close look at your daughter's little rectangular drop-waist dress and you'll recognize the look of the Charleston dress that would dominate only a few years later!

Black was the standard color during the First World War, and the petite Coco Chanel decided to make the most of it and other neutral colors, as well as wartime clothing patterns, and thanks to Chanel's love of simplicity, a low-waist belted shirtdress was created , models of which were shown in Harpers Bazaar in 1916.

This love of sportier, more casual dresses began to quickly spread from the seaside town of Deauville, where she opened a store, to Paris, London and beyond. A 1917 edition of Harper's Bazaar noted that the name Chanel simply never left the lips of consumers.

Paul Poiret's star began to fade with the onset of the war, and when he returned in 1919 with numerous beautiful models in a new silhouette, his name no longer aroused such admiration. Having chanced upon Chanel in Paris in 1920, he asked her:

“Madam, for whom are you mourning?” Chanel wore her signature black colors. She replied: “For you, my dear Poiret!”