The topic of coniferous trees in the culture of Russian post-Finnish territories of Russia and its Finno-Ugric peoples and spruce, in particular, has been studied for a long time, this is confirmed by the mass of scientific works of very competent authors (Shalina I.A., Platonov V.G., Ershov V.P. , Dronova T.I...), each of which is dedicated to the customs and beliefs of the people or their individual group. But there has not yet been such work where a comparative analysis was carried out in order to identify common features in the rituals associated with the cult of the tree, to find those parallels that run like a thin thread through the layers of cultures of the Finnish, Karelian, Komi, Udmurt, Russian North, middle zone Russia (Yaroslavl, Vladimir provinces..), the Urals and Siberia. This article will attempt to conduct such an analysis based on the materials studied on the above topics.

Christ is risen from the dead,

Trampling death upon death,

At the fir trees in outstretched paws,

Wreaths of white baths.

N. Klyuev. "Zaozerye"

We should probably start with the images that we would like to consider, and the main one is the TREE.

Pagan Komi temple in a spruce forest. 60 years of the 20th century.

Cult of trees in Finno-Ugric cultures

The first associations that arise when mentioning this image are the world tree, the axis of the universe. This is true if we consider the tree on a global scale.

But for the peoples of the Finno-Ugric language group, a tree is also an intermediary between the world of people and the world of the dead, the LOWER world of ancestors. The Karelians had a custom of confessing to a tree (1). Among the Verkhnevychegda Komi, they brought a spruce tree to a dying sorcerer, before which he confessed and died without torment (2). According to the observations of ethnographer V.A. Semenov, the Komi considered all trees to be spiritualized (having souls) and associated with the spirits of ancestors; they were associated in popular ideas with a symbolic path to another world (marking the journey of the soul along the world tree).

Attitude to coniferous trees of the Finno-Ugric peoples

Coniferous trees - spruce, pine, juniper, fir, cedar, etc. - were endowed with special sacredness. They symbolized eternal life, immortality, were a receptacle of divine life force, and had cult significance. The New Year's tradition of decorating a Christmas tree goes back to the ancient ideas of the Finno-Ugric peoples that the special vitality and energy of these trees can bring spring closer, helps fertility and promises well-being.

Researcher of the Old Believers in Komi T.I. Dronova writes: “In the worldview of the Pechersk Old Believers, the coniferous forest was associated with the other world. This is indicated by the choice of location for the cemetery - a spruce forest, the ban on walking alone in the coniferous forest, which was called dark” (3).

The spruce forest - the “sacred grove” and the cemetery act as a special locus, as the world of ancestors, which determines its own laws of behavior. Everything in it belongs to the ancestors; here you cannot laugh, make noise, pick berries, mushrooms, firewood, or cut down trees. It can perform healing functions(4). Spruce is a tree of the dead, a tree of another world, it is associated with the cult of ancestors (5).

In the religious and magical beliefs of the Finno-Ugric peoples, spruce was a link between the mythological worlds (living and dead) and therefore was widely used in funeral rites.

The sacred groves of ancient cemeteries in Karelia, Komi and other regions, consisting of coniferous species, mainly spruce - kuusikko (spruce forest), eloquently testify to the fact that spruce belongs to another world and its connection with its ancestors.

In Karelian cemeteries you can often see a spruce tree (cosmic vertical) hung with rags and towels. In the village of Vinnitsa, there was a custom of worshiping a spruce stump in the cemetery (all that, apparently, remained of the cult spruce), to which peasants brought milk, wool, lard, candles and money (6).

The ancient burial ground in the village of Kolodno (16 km from Luga) consisted of fir trees and on one of them hung a stone cross, which peasants used in the treatment of various diseases; the sick crawled over the cemetery chapel three times. “Go to the key and pray in all four directions. Take at least a cross or something else from the patient and hang it on the Christmas tree...” (4).

In Karelian lamentations, the mourner, on behalf of the deceased, asks to prepare for him “beautiful places” (a grave) inside “fir forests flowing with gold” (7).

In Vep funeral rituals, the important role of funeral stretchers is noted (as, indeed, among many other Finno-Ugric peoples), on which the deceased was carried to the grave. They were made from two spruce poles, and after burial they were left on the grave (8). The Udmurts lashed each other with spruce branches when returning from the cemetery so that the spirits would not follow the living to their home. And in the old cemetery in the village of Alozero, in washed-out burials, there are graves in which the deceased was covered with spruce bark (31). When laying the foundation for a new house, the Komi chose a Christmas tree for the lower crown, which was given the symbolism of the “soul of the ancestors,” and therefore the people themselves received the nickname “spruce trees” (9).

The idea of a tree branch as a container for the soul was thoroughly developed by J. Frazer. Interestingly, there are also direct indications of this connection. Thus, in the Dmitrov region in the Moscow region, according to materials from A. B. Zernova, according to local beliefs, the branches that decorate the walls and the front corner of the hut for the Trinity are inhabited by the souls of deceased relatives.

The roofs of the mighty northern houses were supported by structural parts that received a strange name - “chickens”. They were made from spruce rhizomes. Considering that abundant ethnographic materials constantly remind us of the relationship between the chicken and the world of the dead, then, apparently, this name is no coincidence (10).

Why “chicken”? The meaning of this interesting architectural detail still requires study, but a number of meanings can already be identified. The exact functional definition of this detail is given by V. Dahl: “a chicken in the meaning of a hook, a bark for the roof...”. The same definition is given by the Dictionary of the Russian Language of the 9th-17th centuries: “Kur is a device for supporting something, a hook.” But in the peasant consciousness there was a rethinking of this image; it turned out to be connected with the world of their ancestors. Let us remember the “hut on chicken legs”, the Christmas “changelings”: “The hen gave birth to a bull, the little pig laid an egg” - both characters belong to a “different” world; It is a custom at funerals to throw a chicken over the grave. Chicken (dialectal) can mean “blind man’s buff”, a dead person; “chicken god” - a stone with a hole or the neck of a bottle is a hypostasis of the god of the dead (the neck of a ceramic vessel with a living flower on the iconostasis of the Kirik and Ulita chapel near the road in the village of Pochozero, Kenozero) (11).

The chicken motif in spiritual peasant life is widely represented in wedding and funeral rites, “chicken holidays”, in gender terminology, savings magic and fertility magic. The house and the chicken are closely connected in the popular consciousness; straw taken from the roof of the House, like a magical remedy, helps in the reproduction of chickens, and a killed chicken upon entering a new house contributes to the well-being of the owners. The famous researcher of mythological prose N.A. Krinichnaya writes in this regard: “chickens, which have received a semantically significant decorative design, are interpreted in funeral lamentations and beliefs as one of the places where the deceased person embodied in a bird, or rather his soul, is shown for the last time before leaving this world forever.” “The ends of the chicken beams were given the fantastic shapes of a snake with an open mouth or some kind of monster with horns” (11).

Also known among the Finno-Ugric peoples (Karelians, Finns, etc.) is the iconic custom of cutting karsikko - cutting off the branches of a coniferous tree (spruce or pine) in a special way. This topic has been well studied by A.P. Konkka. This multifaceted symbol grows in ritual behavior (funeral, wedding, fishing, etc. rites) to universal categories, and carries the functions of a “mediator between mythological worlds” - the dead and the living (12).

The custom of covering the floor of the room where one says goodbye to the deceased and the road along which the coffin is carried with spruce paws has still been preserved. Spruce branches were a material sign of the life-giving power of the ritual tree (fir), an analogue or substitute for the mythological world tree (13), they were the focus of life-giving natural power” (14). Karsikko sat on cut branches during a ritual meal, with a broom made of coniferous trees they plowed graves in the northern regions of Karelia, green coniferous branches were thrown into the hem of the young housewife, which should contribute to family happiness and the birth of children, with a broom made of coniferous branches they swept under the stoves and took it to a stable for the sheep to lamb (14). A coniferous branch, decorated with ribbons, was carried in a sleigh with a scarecrow of Maslenitsa, or a spruce tree was carried in special firewood on Maslenitsa in some northern areas of Russian settlement and in the Volga region (15). A coffin was made from spruce or pine boards.

Wooden pine coffin,

Built for me...

(Spiritual song of the Old Believers)(16).

Among the Pechersk Old Believers, the coffin was indeed made of spruce (17).

V.G. Bryusova, having examined a chapel in the Karelian village of Manga (a monument of the 17th-18th centuries), writes: “Icons of local letters were mostly written on pine or spruce boards...” (18). The same phenomenon is noted in Siberia - folk icons there were also painted on spruce (19). Is this a coincidence? Did the type of wood have a sacred meaning? Karelian art critic V.G. Platonov, based on previous studies by I.A. Shalina(20), V.G. Bryusova, N.N. Voronin, puts forward the theory that the icon he analyzed from the Assumption Chapel in the village of Pelkula “The Descent into Hell with the Deesis Order” reflected in the iconography “the essential features of the ancient funeral and memorial rite”, “is associated with the funeral and memorial rites that took place in the chapel and in the cemetery near the village of Pelkula” (21).

Analyzing the collection of primitive folk icons from the same chapel, Ershov V.P. came to the same conclusions about their funeral and memorial function (22). Each character in the icon “takes care” in one way or another about the well-being of the dead in another world, and through them, about the living.

To be continued...

Author - Olga Kokueva. "Metsa Kunnta" Moscow.

1. Konkka A.P. Karelian and East Finnish karsikko in the circle of religious and magical ideas associated with wood // Ethnocultural processes of Karelia. Petrozavodsk, 1986. 20. Bryusova V.G. On the Olonets land. M., 1972.

2. Ilyina I.V Komi-Karelian parallels in religious and magical ideas about spruce // Karelians: ethnicity, language, culture, economics. Problems and ways of development in the conditions of improving interethnic relations in the USSR. Petrozavodsk, 1989.

3. Dronova T.I. Earthly existence - as preparation for the afterlife (based on ethnographic materials from Ust-Tsilma) // Christianity and the North. M., 2002.

4. Panchenko A.A. Folk Orthodoxy. St. Petersburg, 1998.

5. Ershov V.P. Board for an icon // Ours and others in the culture of the peoples of the European North. (Materials of the III International Scientific Conference). Petrozavodsk, 2001.

6. Tishchenko E. Ideas about trees in the rituals and beliefs of the inhabitants of Karelia // Problems of archeology and ethnography. Palace of Children and Youth Creativity. Petrozavodsk, 2001. Issue 3.

7. Konkka U.S. Poetry of sadness. Petrozavodsk, 1992.

8. Strogalshchikova Z.I. Funeral rituals of the Vepsians // Ethnocultural processes in Karelia. Petrozavodsk, 1986.

9. Semenov V.A. Maypole in the folk culture of the European northeast. (Theses) // Oral and written traditions in the spiritual culture of the people. Syktyvkar, 1990.

10. Uspensky B.A. Philological research in the field of Slavic antiquities. M., 1982.

11. Krinichnaya N.A., 1992, P. 6//Kenozersky readings.

12. Konkka A.P. Karelian and East Finnish karsikko.

13. In the Karelian and Finnish runes, the world tree appears in the form of a spruce with a “golden top” and golden branches: At the top the moon shines / And the Bear on the branches / At the edge of the Osmo clearing (Kalevala / Trans. Belsky R.10).

14. Konka A.P. Karelian and East Finnish karsikko.

15. Maksimov S.V. Unclean, unknown and godlike power. St. Petersburg, 1903.

16. Zenkovsky S. Russian Old Believers. M., 1995.

17. Dronova T.I. Earthly existence is like preparation for the afterlife...

18. Bryusova V.G. On the Olonets land. M., 1972

19. Velizhanina N.G. Folk icons of the Novosibirsk region from the Novosibirsk Art Gallery // Museum-4. Art collections of the USSR. M., 1983.

20. I.A. Shalina, studying the early Pskov icons, which depict saints identical to the icon from the Assumption Chapel in Pelkul (“The Descent into Hell, with the Deesis Order”), came to the conclusion that “the saints represented on the Pskov icons are united by one common feature: all they are somehow connected with thoughts about death, the afterlife and the salvation of the righteous...", and the icons themselves "served in ancient times as unique memorial images and were part of the complex of temple tombstones."

21. Platonov V.G. Segozero letters // The village of Yukkoguba and its surroundings. Petrozavodsk, 2001.

22. Ershov V.P. Savior-progenitors // Ibid.

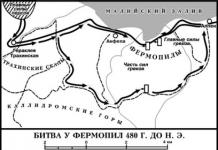

Settlement of Finno-Ugric peoples

Finno-Ugric mythology is the general mythological ideas of the Finno-Ugric peoples, dating back to the era of their commonality, that is, to the third millennium BC.

A peculiarity of the Finno-Ugric peoples is their widespread settlement around the world: it would seem, what do the inhabitants of the European North - the Finns, the Sami - have in common with the inhabitants of the Urals, the Mordovians, the Mari, the Udmurts, the Khanty and the Mansi? Nevertheless, these peoples are related, their connection remains in language, customs, mythology, and fairy tales.

By the first millennium BC, the ancient Finno-Ugric peoples settled from the Urals and Volga region to the Baltic states (Finns, Karelians, Estonians) and northern Scandinavia (Sami), occupying the forest belt of Eastern Europe (Russian chronicles mention such Finno-Ugric tribes as Meri, Murom , miracle). By the ninth century AD, the Finno-Ugrians reached Central Europe (Hungarians).

In the process of settlement, independent mythological traditions of individual Baltic-Finnish peoples (Finnish, Karelian, Vepsian, Estonian), Sami, Mordovian, Mari, Komi, Ob Ugrians and Hungarian mythologies were formed. They were also influenced by the mythological ideas of neighboring peoples - the Slavs and Turks.

World structure

In the oldest common Finno-Ugric mythology, cosmogonic myths are similar - that is, stories about the creation of the world. Everywhere it is told how the demiurge god, that is, the creator of the world, orders a certain waterfowl or his younger brother, who has the appearance of such a bird, to get some earth from the bottom of the primary ocean. They talk about how the demiurge god creates the world of people from the earth obtained in this way. But the younger brother - usually the older brother's secret rival - has hidden some dirt in his mouth. From this stolen soil he creates various harmful things, for example, impassable mountains. In dualistic myths, the “companion” of the creator god in creating the world is not his younger brother, but Satan.

In another version, the world is created from an egg laid by a waterfowl.

In all Finno-Ugric mythological systems, the world is divided into upper, middle and lower parts. Above is the sky with the North Star in the center, in the middle is the earth, surrounded by the ocean, below is the afterlife, where there is cold and darkness. The upper world was considered the abode of heavenly gods - such as the demiurge and the thunderer. The earth was embodied by female deities, who often became the consorts of the heavenly gods. Marriage between heaven and earth was considered sacred. On earth lived the owners of forests, animals, water, fire, and so on. The creator of all evil has settled down in the lower world, among the dead and harmful spirits.

For Finnish mythology, the name “Yumala” is extremely important: it is a general name for a deity, a supernatural being, primarily a celestial one. The very name of the deity - “Juma”, “Ilma” - is associated with the name of the sky, the air. Often this word was used in the plural to refer to spirits and gods in general, collectively. After the Christianization of the Baltic peoples, “Yumala” began to be called the Christian God.

The mysterious country of Biarmia

Residents of the North have always considered those who live even further north to be sorcerers - after all, they are very close to the afterlife, one might say, they can easily enter there. The Slavs considered the Finns to be sorcerers, the Finns themselves considered the Sami to be powerful sorcerers - and so on. The Scandinavian sagas preserve stories about the travels of the Vikings to a magical land inhabited by certain Finno-Ugric peoples (naturally, powerful magicians).

Icelandic Normans have long known about the existence of the mysterious Biarmia - a country inhabited by sorcerers and possessing untold riches. One of them, named Sturlaug, went there to get the magic horn Urarhorn, sparkling like gold and full of enchantments.

Sturlaug decides to get hold of this wonderful item at any cost and, together with his comrades, sets off on the journey. Fate brings them to the country of the Hundings - man-dogs living on the edge of the Earth. The Hundings grab the Icelanders and throw them into the caves. However, Sturlaug managed to get out and lead his comrades out.

And so the Vikings reached the main temple of Biarmia, where an image of Thor appeared before them. The idol was on a dais, in front of it stood a table full of silver, and in the midst of these riches lay Urarhorn, filled with poison. Luxurious robes and gold rings were hung around on poles, and among other temple treasures, the Icelanders discovered golden chess sets.

Thirty priestesses served in the temple, and one of them was distinguished by her enormous height and dark blue skin. Noticing Sturlaug, she uttered a visu-curse: in vain the aliens hope to take away the golden rings and Urarhorn - the villains will be ground like grain. The path to the altar was blocked by stone slabs, but Sturlaug jumped over them and grabbed the horn, and another Viking, Hrolf, took the golden chess.

The priestess rushed after Hrolf and threw him so hard against the flagstones that he broke his back. But Sturlaug with the horn ran to the ships. The giantess overtook him, and then he pierced her with a spear.

Another saga about the interaction of the Vikings with the inhabitants of the north of Eastern Europe - the Biarms, a people of sorcerers - “The Saga of Halfdan Eysteinsson” - tells how the Vikings fought in battle with the Biarms and Finns. The Finnish leader Floki, for example, shot three arrows from a bow at once - and all three hit the target, hitting three people at the same time. When Halfdan cut off his hand, Floki simply placed the stump against the stump, and the hand became unharmed again. Another Finnish king turned into a walrus and killed fifteen people.

Icelandic historian and skald Snorri Sturluson also describes a journey to Gandvik - the “Witch Bay” (as the White Sea was called in medieval Scandinavia). At the mouth of the Vina River - Northern Dvina - there was a trading center of the Biarms, and the Viking leader Thorir, instead of trading, decided to simply profit there. He knew that, according to the customs of the Biarms, a third of everything that the deceased owned was transferred to the sanctuary in the forest under the mound. Gold and silver were mixed with soil and buried.

So the Vikings penetrated the fence of such a sanctuary. Thorir ordered not to touch the deity of the Biarms, who was called Yomali, but to take as much treasure as he could please. He himself approached the idol of Yomali and took the large silver bowl that was on his lap. There were silver coins in the bowl, and Thorir poured them into his bosom. Seeing how the leader was behaving, one of the warriors cut the precious hryvnia from the neck of the idol, but the blow was too strong, and the god’s head flew off. There was a loud noise, as if the idol was calling for help, and soon an army of Biarms appeared. Thorir, fortunately, knew how to make himself and his companions invisible: he sprinkled ashes on everyone, and at the same time sprinkled ashes on the tracks, and the Biarms did not find the newcomers.

Finnish deities

Almost no myths have survived that would coherently tell about the Finnish and Karelian gods. It was not until 1551 that the Protestant bishop Mikael Agricola, head of the Finnish Reformation, began to collect what little information remained about the gods of the pagan Finns.

Bishop Mikael Agricola was born around 1510 and lived less than fifty years, but he is called one of the “creators of the Finnish language” - primarily due to his educational activities and translation of the Bible into Finnish. He carefully studied the superstitions in which his people lived, and wrote down the legends and names of gods, the belief in which the Catholic Church could not eradicate (to some even the gloating of the reformer bishop).

In the old days, he says, the Finns worshiped the forest deity Tapio - he guides rich game into the traps set by hunters. The god of waters, Akhti, provided similar services to people. Magic songs were composed by Einemöinen (in this name it is easy to recognize the ancient name “Väinämöinen”). There was also an evil spirit named Rahkoy, who controlled the phases of the moon (apparently, every now and then he ate a piece of the moon, and at the same time caused lunar eclipses).

Herbs, roots and plants in general were ruled by a deity named Liecchio.

Ilmarinen, who was credited with creating the entire world and, most importantly, the air (he was generally the patron of the air element), monitored the weather. And, in particular, it was to this deity that a request should be made so that the trip would be successful.

Turisas was called the patron saint of warriors, granting victory in battles.

Finnish beliefs preserve the myth of the thunder god Turi, who killed a giant boar with his ax or hammer.

A person's property (and his goods) was handled by Cratti, and the household by Tontu. However, this pagan deity (according to the bishop - an ordinary demon) could drive him into rage. And in fact, according to legend, house and barn spirits really had the power to punish careless owners with illnesses and other misfortunes.

We see how pagan and once undoubtedly powerful gods are gradually relegated to the level of spirits, gods, characters of lower mythology and folk superstitions.

Thus, the barn - the spirit of tonite - is born from the ritual last sheaf, which is usually kept in the barn. If the tonite creaks, it means it will be a fruitful year; if it is silent, it means the year will not be very good. Tonitu is an enrichment spirit: he can steal grain from his neighbors for his masters.

In addition to the names of the gods, Bishop Agricola also names the names of Karelian idols, including the harvest god Rongotheus (in Finnish folklore this is the “father of rye” Runkateivas). In principle, the Finno-Ugric people generally worshiped a wide variety of vegetation spirits: almost every culture had its own patron god (rye, oats, barley, turnips, peas, cabbage, hemp, and so on).

The plant spirit Sampsa Pellervo is known in Finnish folklore. In the spring, this young god is awakened by the sun, and when the sun wakes up, seedlings begin to rise.

Sampsa lives on the island with his wife - Mother Earth herself. In some legends, the Son of Winter is sent after him, who arrives on the island on a wind horse. Sampsa returns to earth, the sun awakens - and summer comes.

In addition to Sampsa, fertility was patronized by the heavenly god Ukko and his wife Rauni. In Finnish ideas, Ukko is included in the group of “upper” gods: the general Finnish heavenly deity Yumala, the thunderer Turi, Paianen and the god of air and atmosphere Ilmarinen (who in later Karelian-Finnish runes takes on the features of a cultural hero - a blacksmith).

Fertility of livestock, according to Agricola's description, was promoted by the god Kyakri (or Keuri). The same word - “keuri” - is used to describe the Finnish holiday associated with the commemoration of the dead in early November, when grain threshing ends and summer gives way to the “throne” of winter. “Keuri” was also the name of the shepherd who was the last to bring in the cattle on the last day of grazing, and the last reaper during the rye harvest.

On the Keuri holiday the dead returned to the world of the living; a bathhouse was heated and a bed was made for deceased ancestors. If you accept the spirit of your ancestors well, they will ensure the harvest and fertility of livestock.

Bishop Agricola also noted the gods who, according to the Finns, patronize hunting and fishing. So, in the forest the hunter is helped by a god named Hiisi. For squirrel hunters there was their own god - Nirkes, for hare hunters there was another god - Hatavainen.

There were also goddesses: Kereytar - the golden wife, mother of foxes; Lukutar is the mother of silver foxes; Hillervo is the mother of otters, Tuheroinen is the mother of minks, Nokeainen is the mother of sables, Jounertar is the mother of reindeer. Perhaps all these “mothers” were the daughters of Tapio, the owner of the forest. The flocks of wild birds were tended by a separate goddess - the old woman Holokhonka (or Heikheneikko).

Mikael Agricola, who carefully wrote down all these names, sighed sadly: despite the existence of the Christian faith, the Finns continue to worship false gods, as well as stones, stumps, stars and the moon.

Creation of the world and man

According to the ideas of the ancient Finno-Ugrians, the world arose from water. At first there was an endless ocean, and a bird flew over it in search of a nest. What kind of bird it was - versions are different: sometimes it is a duck or a goose, there are myths where a swallow, an eagle, and so on appear.

And then the bird noticed some firmament on which it could land. This was the knee of the first human being, and it rose above the water. Some runes tell us the name of this creature - the heavenly maiden Ilmatar, the mother of Väinämöinen. In other legends, this is Väinämöinen himself, and the Finnish runes about the creation of the world explain his presence in the waters of the World Ocean with a rather strange circumstance: the fact is that an evil Sami sorcerer shot at him with a bow, so that Väinämöinen floated on the waters like a spruce log for six years.

The bird dropped to this knee and laid an egg or three eggs. The heat from the eggs was so intense that Väinämöinen could not stand the heat and shook them off his knee. The eggs rolled down, fell and broke, and from the building material of eggs, that is, the yolk, white and shell, the world was created.

There are legends that the bird laid three eggs, and they were swallowed by a pike, a hostile creature from the underground (water) world. But the bird still caught the pike and ripped open its belly, pulling out at least one egg. From the upper half of the egg the sky was created, from the lower half the earth, from the yolk the sun, from the white the moon, from the shell the stars, and so on.

In most myths, during the creation of the world, a certain blacksmith of “primordial times” is present. In Karelian-Finnish runes he bears the name Ilmarinen - this is the name of the ancient deity of the air. The blacksmith Ilmarinen, the air maiden Ilmatar, and the bird itself are all creatures belonging to the cosmic element. In some myths, the blacksmith forges the firmament, creates the sun and the moon after the demonic mistress of the North (the mistress of Pohjola, the ruler of the world of the dead) steals the originally existing luminaries. An even more ancient myth is also known, according to which a blacksmith helped to extract the stars from the bottom of the World Ocean - and he also attached them to the sky.

The specificity of Finno-Ugric cosmogony also lies in the fact that the myth of the origin of man almost completely repeats the myth of the creation of the world.

The Finnish rune tells the story of a girl who emerged from a duck egg laid by a bird in a swamp. This girl was named Suometar - that is, “Daughter of Suomi.” “Suomi” is what the Finns call their land, therefore, we are talking about the foremother of the Finnish people.

Six months later, she turned into a beautiful bride, and the Moon, the Sun and the son of the Polar Star came to woo her.

The month was the first to be rejected by her, because Suometar considered him too fickle, because he changes all the time: “now his face is broad, now his face is narrow.”

But the Sun with his golden mansions turned out to be not good enough for the Daughter of Suomi: he has a bad character. It is the Sun that burns the crops, then suddenly hides and allows the rain to “spoil haymaking time.”

She only likes the son of the Polar Star, and she agrees to marry him.

And this is not without reason, since it is the North Star in Finno-Ugric mythology that represents the center of the entire celestial world. This is a “nail”, a “rod” around which the firmament rotates. And having become the daughter-in-law of the North Star, the foremother of the Finnish people places herself at the very center of the universe. Thus, in Finnish mythology, man actually occupies a central place in the universe.

Three-part world

Like many archaic peoples, the Finno-Ugrians considered the world to be tripartite - consisting of three parts: upper, middle and lower. The upper and lower worlds, in turn, were three-layered; therefore, in Finno-Ugric mythology, the universe appears to consist of seven layers.

The middle world, the world of people, the earth is round. It lies in the middle of the waves of the World Ocean and is covered with a rotating sky.

The fixed axis of the sky is the North Star, the “Nail of the Earth.”

The firmament is supported by a mountain - copper, iron, stone (in different Finno-Ugric mythological systems the mountain can be described differently) or a huge oak tree, whose peaks also touch the North Star.

The oak was planted by three maidens, similar to the goddesses of fate from Scandinavian mythology. There is also a myth that this oak tree - the World Tree - grew from the foam skimmed off after brewing beer. Beer was a sacred drink among the Finno-Ugrians.

They also say about this oak tree that its huge crown obscured the sun and moon and did not let their light onto the earth. And then a magical dwarf came out of the sea and cut down the oak tree with a single blow of his hatchet. After this, the World Tree collapsed and turned into the Milky Way, which united all parts of the Universe. The felled oak tree is also a bridge across which one can pass from the world of the living to the world of the dead.

Pohjola

In the north, where the sky touches the earth, is the land of the dead. The Finns call it the “North Country”, Pohjola, the underworld. A river separates her from the world of the living, but instead of water, fire rushes along the riverbed (or, in other versions, a stream of swords and spears). You need to cross the thread bridge - only to meet the guardian of the land of the dead, whose iron teeth and three guard dogs inspire the traveler with natural fear for his fate. The gates can only open for those who have been properly mourned by their relatives with appropriate lamentations.

The embodiment of death, the owner of the kingdom of the dead, Tuoni, sends his daughters on a boat to pick up the dead man, and the sons of Tuoni weave iron nets so that the dead man or the shaman cannot escape back to freedom, back to the kingdom of the living.

All healers and sorcerers take their secret knowledge here, so the hero Väinämöinen had to penetrate into the kingdom of the dead when he needed magic words. This is where our ancestors live.

And at the same time, Pohjola is a country of forest and water abundance. From here game and fish enter the human world: their owner drives them from the far north to human habitats.

In the south of the World Ocean there is an island where dwarfs live. This island is called Linnumaa - “The Land of Birds”. This is where birds fly across the Milky Way when winter sets in.

A giant whirlpool hides in the very heart of the World Ocean. It releases and absorbs water, causing the ebb and flow of tides.

Thunderer Ukko

Ukko is the supreme god, the thunderer, common to all Baltic Finns. Estonians call him Uku, his other names are Vanamees, Vanem (“old man”, “grandfather”).

Ukko is an old man with a gray beard. Wearing a blue cloak (blue like clouds), he rides a chariot along the stone heavenly road. Ukko's main attribute is lightning. An ax (sometimes stone), a sword, a club are his weapons. Ukko hits the tree with his golden club (lightning) and strikes fire.

Ukko's "thunder claws" are associated with a very ancient idea of the thunderbird. With these stone claws he carved out heavenly fire, which - on earth - went to Väinämöinen. Ukko rolls heavenly stones (thunder) and strikes evil spirits with lightning, who can only hide from him in water. Ukko's bow is a rainbow, his arrow is a sliver from a tree broken by lightning (to find such a sliver means to find a talisman endowed with very great power).

The sanctuaries of Ukko were groves and stones, to which they prayed for healing from illnesses and for a good harvest (as the “weather” god Ukko was undoubtedly associated with fertility). Ukko is the patron of hunters, especially in winter: he sprinkles the ground with fresh snow so that people can see traces of the game that has recently passed. Ukko will help you track down the hare and defeat the bear.

Ukko is not only a thunderer, but also a warrior, therefore he is the “Golden King”, who will dress the warrior in impenetrable chain mail, give him a fiery fur coat, and invincibility in battle.

The opponent of the Thunderer in Finnish folklore could be called "Perkele". The Finns borrowed this name from the Balts, who named their own thunderer with the name Perkunas. Among the Finns, the neighboring deity thus turned into its opposite.

We remember that the Finnish gods were described in the sixteenth century by Bishop Agricola. This pious man was especially outraged by the family relationship between Ukko and his wife Rauni. By the way, there is an assumption that “Rauni” is not the name of the goddess at all, but an epithet of Ukko himself, the word “fraujan” borrowed from the Old Norse language with the meaning “lord”. Another hypothesis for the origin of this name is related to the Finnish word “rauno” - “pile of stones” (stones are an important attribute of Ukko).

As Agricola writes, after the end of sowing, the peasants drank beer from a special “Ukko cup” and got drunk. Women also took part in the outrages. The feast was dedicated to the marriage of Ukko and Rauni and “various lewd things” happened there.

Rauni has a grumpy character, and when she swears, God begins to get angry: thunder rumbles from the north - it is Ukko growling. After the rain, seedlings rise, the quarrel of heavenly spouses serves as the key to a good harvest.

As an “old man”, Ukko is associated with the cult of ancestors; as a thunderer, he gradually began to merge with the image of Elijah the Prophet, as well as with the image of the Apostle Jacob - Jacob, who is nicknamed “the son of thunder.”

The celebration of the Apostle James on July 25 was called “the day of Ukko.” According to the sign, what the weather is like on this day - it will last like this throughout the harvest and throughout the fall. It is strictly forbidden to work on the day of Ukko: the deity can punish by striking the house of the disobedient with lightning.

In other places, the day of Ukko was celebrated on the day of the prophet Elijah and beer was brewed to bring about fertile rain.

Forest deities

Hiisi is an ancient spirit worshiped by all Baltic Finns. This is, on the one hand, a giant elk, and on the other, a spirit that lives in a sacred grove and is associated with the kingdom of the dead.

The dead were once buried in the Hiisi Grove. There it is forbidden to break branches and cut down trees; sacrifices were brought there - food, beer, wool, clothes, money. The “House of Khiisi” was once called the afterlife, the country of the North, and the “people of Khiisi” were the souls of people who did not find peace and refuge in the afterlife. A traveler may encounter a whole crowd of headless monsters on the Hiisi trail, moving in a whirlwind or on horseback; it is dangerous for the sanity of a living person.

Birch, pine, spruce - these trees can be iconic for Hiisi. In addition, in ancient times, giants made mounds of huge stones - these are also “Khiisi stones”. These giants were very powerful - they could throw a stone so large that they killed two bulls at once. A stone thrown by the giant-hiisi became a threshold on the river. Lake reefs are bridges that were not built by giants (they started the work but did not finish).

Hiisi himself is enormous in size. He has a wife and children; in fairy tales, the daring guy tries to woo Hiisi’s daughter and performs various difficult tasks for the sake of the bride.

Gradually, Khiisi turned from a deity into a goblin, an evil spirit, and the “Khiisi people” began to be called evil spirits. The whirlpools and waterfalls are home to underwater hiisi (these hiisi have wonderful cattle, and a brave person can steal a wonderful cow when it comes out of the lake).

Khiisi's arrows bring illness to people, and "Khiisi's Horse" brings plague. However, Hiisi’s patronage can also be useful for a person: like any goblin, he is able to save a traveler and send rich prey to the hunter.

The Khiisi giants are afraid of the ringing of bells and seek to destroy the church under construction.

Unlike the evil Hiisi, the owner of the forest, Tapio, always remained the “golden king of the forest,” the “gray-bearded old man of the forest,” and the patron of forest crafts. They ask him for help in the hunt. Small offerings are left on the “Tapio table” - a stump. The forest country is called "Tapiola".

Tapio's wife was Mielotar, Mielikki - the "mistress of the forest", capable, at the request of a hunter, of opening a honey chest and releasing a gold and silver beast, or even bringing rich hunting prey from Pohjola itself.

The Tapio children - “forest boys and maidens” - helped preserve the cattle grazing in the forests.

Bishop Agricola also mentions in his notes the water god Ahti - the patron of fish and seals, the one who owns all the riches of the waters, the “golden master of the sea” of runic songs. He was depicted as an old man with a green beard. He wears silver robes that look like scales. Sometimes Ahti appears in the guise of a fish. The sea is called “Akhtola”, and this is the barn of the god Akhti.

The water goddess Vellamo was considered the wife (or daughter) of Ahti. Väinämönen himself tried to catch her and marry her, but without any success. And this despite the fact that Väinämöinen had a kantele, a wonderful stringed instrument made from the backbone of a giant pike. When Väinämöinen played the kantele, all the inhabitants of the sea and land inevitably listened to the magical music. Playing the kantele was supposed to attract Ahti's pets online.

As a water deity, Ahti is also connected to the other world and is asked to heal illnesses.

The Finns and Karelians had other water spirits that could appear to people in the form of a fish, a dog, a foal, a goat, and even a frightened hare (being carried away by pursuit, a person risks falling into the sea and drowning). It is dangerous to meet a one-eyed fish in the waves, because it can knock a fisherman off the boat into the water with its tail. If you catch one in a net, it will cause a storm.

Small water spirits can drag a person under water, so if you come across a log, you should take a close look to see if it has one eye. One-eyed logs are very dangerous for humans, because if the poor fellow who has been castaway tries to grab onto one, it instantly sinks along with the “rider.”

Among the riches of water spirits that man seeks to acquire, the first known are herds of wonderful animals, most often cows. At night they come out of the waters to graze, and then they can be captured if you manage to run around the entire herd or throw an iron object into the water.

Origin of sacred animals

A number of legends tell how various realities of the external world came about (or were created) - luminaries, fire, iron, tools. The oldest among this category are the myths about sacred animals, the first of which is rightfully considered the giant elk Hiisi.

Hiisi is the name of a deity associated with the forest. As we remember, its constant attribute is its enormous size; it is a giant. Such is he in the form of a moose rushing across the sky. A hunter on skis is chasing the moose Hiisi, but he can’t catch up with his prey. In the end, the hunter turns into the North Star, the ski track becomes the Milky Way, and everyone can see the moose in the sky in the form of the constellation Ursa Major.

In the Karelian-Finnish runes, this hunt is attributed to various heroes, one of which is the “cunning guy Lemminkäinen.” This is a bright character: despite a certain “coolness,” he constantly fails.

So, one day Lemminkäinen made wonderful skis. These skis turned out to be so good that not a single living creature could escape the hunter, no matter where he chased him through the forest.

Of course, there was no need to boast about this, and even so loudly: the owners of wild creatures, Khiisi and other spirits, heard the hero’s speeches and, to spite him, created the elk Khiisi: the head - from a swamp hummock, the body - from dead wood, the legs - from stakes, the ears - from lake flowers, eyes from marsh flowers.

The magic elk ran north - to Pohjola, where he caused mischief: he knocked over a cauldron with fish soup. The women began to laugh at this confusion, and the girls, on the contrary, burst into tears. Lemminkäinen decided that the women were mocking him, the most dexterous hunter in the world, and chased Hiisi the moose on his wonderful skis. In three leaps he overtook the elk and jumped onto its back. And so he dreamed of how he would skin the prey, lay this skin on the wedding bed and caress the beautiful maiden there.

There was no point in dreaming about the unskinned skin: Lemminkäinen was distracted, and the elk took advantage of his absent-mindedness and ran away. The hero set off in pursuit again, but in his haste he broke his skis and poles.

Why did Lemminkäinen suffer such an unfortunate failure? Because he violated two prohibitions at once: firstly, prey is scared away by thoughts of marital pleasures, and secondly, the skin of a sacred animal cannot be used in everyday life.

There are several versions of the myth of the celestial hunt. In another case, the hunter is no longer pursuing an elk, but a cosmic bull, so powerful that even the gods themselves are not able to kill it.

The cosmic bull is truly huge: a swallow will fly between its horns all day long. When the gods decided to kill the bull, the supreme deity himself, Ukko, appeared, other gods helped him, but the bull scattered them with one movement of his head.

Only the blacksmith Ilmarinen is able to defeat the bull, but he did not succeed the first time. Only having obtained a huge hammer, Ilmarinen killed the bull with a blow to the forehead, after which the animal was boiled in a cauldron and its meat was fed to all the people of Kaleva.

In similar myths about a giant bull or boar, the opponent of the beast is not the supreme god or a cultural hero, but an old man, a little man who comes out of the sea.

Finally, one can come across a legend that the bull (boar) was defeated by the thunder god Tuuri, in whose image one can see the features of the Scandinavian Thor.

The sacrifice of a bull for a communal feast is a very old motive. And even a hundred years ago, the Karelians staged a “bull slaughter” at Christmas time: they dressed some old man in an inverted fur coat, put on a mask with horns, and instead of a hat, a bowler hat, and in this form they led him around the courtyards. The mummers walked around the village, the “bull” roared and scared the women and children. In the end, he was “killed” by hitting the pot - and after that a general feast began, and the “bull” was seated in a place of honor. Such a ritual, obviously, was supposed to provide the entire community with abundant food for the whole year.

It is interesting to note that in a number of cases the sky bull comes to replace the sky elk: obviously, such a replacement to some extent symbolizes the transition from hunting to cattle breeding.

Bear

Another revered animal among the Finno-Ugric peoples is the bear. Various legends have been preserved about the origin of this beast. One of the myths says that he was born near the constellation Ursa Major and was lowered down on silver straps in a gilded cradle straight into the forest. Another version says that the bear arose from wool thrown into the water from heaven.

During a bear hunt, the animal is usually convinced that he was not killed by the hunter at all, but came to people’s houses of his own free will and brought them his belly filled with honey as a gift. The bear was generally perceived as a relative of a person, hence the numerous stories about the “bear wedding”, which eventually “migrated” into fairy tales about a girl who married a bear and lived with him in love and harmony. Archaeologists made an amazing discovery in 1970 in one of the mounds where two women were buried. Next to one of them, a young girl, they found the remains of a real bear’s paw, with a silver ring on her finger. It was believed that girls who died before marriage did not live a full life and after death could become especially dangerous and even turn into evil spirits. Perhaps this is why the deceased girl was betrothed to a bear after the coffin - this will help avoid the grim consequences of her premature death.

In general, amulets in the form of a bear's paw, artificially made or real, were very common in the Finno-Ugric world. Claws were believed to be necessary for the shaman to climb the World Tree (or World Mountain) and reach worlds beyond human reach.

In some myths, the bear acts as a mount of the sun, in others it is considered the son of a pine tree - hence the custom of hanging the skull of a killed bear on a pine tree, that is, returning it to its mother: they believed that after such a ritual the bear would be reborn to life.

Unclean creatures

In addition to cosmic sacred animals, the world is full of evil creatures. The evil sorceress Suetar has flooded the world with all kinds of evil spirits. It was she who gave birth to blood-sucking insects, and from her spit into the sea snakes were born.

Suetar is something like a Baba Yaga, she resorts to magic to get into the world of people and harm them to the best of her ability.

A bizarre tale that retains the features of an etiological myth (that is, the myth about the origin of animals and things) tells how various harmful birds arose.

One woman had nine sons and was expecting a child again. She agreed with her children that if a girl was born, she would hang a spinning wheel on the gate, and if she had a son again, then an ax. A daughter was born, and the mother hung a spinning wheel on the gate. However, the witch Suetar changed the omen and put an ax instead of a spinning wheel, after which the sons left home and decided not to return. Obviously, they considered that the tenth boy in the family was too much.

Years passed, the daughter grew up, and her mother told her about how the witch deceived her brothers. The girl decided to find them, for which she baked a bun mixed with her own tears. The bun rolled along the road, pointing the way to the brothers.

But in the forest the girl met the witch Suetar, and she made her an offer that was difficult to refuse: “Spit in my eyes, and I’ll spit in you.” After this action, the witch and the girl exchanged appearances: the beautiful sister turned into an old woman, and the Finno-Ugric Baba Yaga into a beautiful sister. In this form they appeared to the nine brothers.

Having finally learned the truth, the brothers forced the witch to return her sister’s mind and her former appearance (by spitting in her eyes again), and Suetar herself was lured into a pit and burned there. Dying, the witch managed to turn her body into birds that harm people: magpies flew out of her hair, sparrows from her eyes, and crows from her toes. All these creatures are called upon to peck at the harvest and eat the goods of good people.

Pike and snake are considered harmful creatures in Finnish mythology. They are related to the underworld, to the kingdom of the dead. The frog is also one of the very unpleasant creatures. In particular, sometimes the frog replaces human children with its own cubs.

In addition to very real animals, which in one way or another interfere with a person’s housekeeping, the Finns were “hampered” by numerous spirits.

According to Finnish legends, there was a whole magical people - “inhabitants of the earth”, “earth people”, “underground people”: Maakhis, Maanveki, Maanalays.

These creatures are similar to people, but they differ in some special ugliness, for example, a foot turned backwards. However, their daughters can be exceptionally beautiful.

Maakhis are able to change their appearance and turn into frogs, lizards, and cats. They live in the underground world, but can live in hills, wastelands, and forests.

The road leads to their habitat along ant trails and across lakes.

At home, in the underworld, maakhis walk upside down, moving along the reverse surface of the earth.

A person can sneak into their country, and then an important rule must be observed: under no circumstances should you eat or drink anything there, otherwise there will be no way back. Returning to the human world, such a wanderer may find that a year spent with the Maakhis is equal to fifty years in the ordinary world.

If a person gets lost in the forest, the danger for him to get to the maakhis is very great, so you need to take measures in advance: for starters, turn your clothes inside out, otherwise what is right may turn out to be left for him and vice versa (maakhis are masters at fooling people). Next, they should be appeased by leaving some offering (honey, grain, milk) on the Maakhis trail.

The Maakhis kidnap children, leaving deformed changelings in their place. But they also have something that people would like to take possession of - wonderful cattle. If you manage to capture a Maakhis cow, you are guaranteed wealth. To do this, you should waylay a herd of maakhis and throw an iron object (key, button, needle) at the animals.

Marriages between humans and maakhis are possible. It is especially advisable to marry your daughter to the Maakhis: your new relatives will provide you with rich gifts.

In the human world, the Maakhis primarily look after livestock. If a person mistreats their pets, the maakhis will intervene and punish the culprit. Well, if a person accidentally built a barn over their underground dwelling, they can come and politely ask to move the structure, since sewage flows from there onto their heads. The Maakhis must be respected, otherwise the consequences may be very unpleasant for a person.

Host spirits

Karelians and Finns also believed in the master spirits of water and earth, forests and mountains, the owners of the hearth and the owners of the bathhouse.

The owner of the hearth usually takes the form of the one who first lit the fire in this hearth. Sometimes the house owner (and mistress) have a strange appearance: one eye in the forehead, for example. Many people wear a red cap with a tassel. The brownie is usually the one who died first in the new house.

The boats also had their own master spirit. A special spirit - the “master of the boundary” - ensured that the boundaries between the fields were drawn correctly. If a rogue land surveyor made an incorrect division, such a spirit could come to him shouting: “Rectify the boundary!” Sometimes the rogue land surveyor himself becomes the spirit who wanders around and cannot find peace.

Pyara milks the neighbor's cows and steals milk and butter from others for her owners. It’s not difficult to create such a “miner”. You need to bring a spindle with a drop of the owner’s blood into the sauna. This blood will help revitalize the spindle. Having become alive, such a spindle makes its way into the neighbor's yard through a hole in the fence - and does its tricky job.

Another appearance of the pyara is a black bird with a large belly. In this belly, the pyara carries goods into the house of its owner. Pyara can also look like a cat or a frog - this indicates the harmful nature of this spirit.

By the way, if you kill such an animal, then the owner of the bird dies along with it. So if you decide to use a spindle and a drop of your blood to start stealing from your neighbors, then the consequences are at your expense.

Finnish beliefs also include the idea of mortal power - kalma. This is the embodiment of death, a certain power emanating from the dead. Kalma is embodied in objects that came into contact with the deceased. Sorcerers can use a purse containing cemetery soil to cause damage. The deceased may take several more people with him to the grave, so after the funeral certain rituals must be performed.

The spirit of the hearth, which lives in the oven, usually protects against the mortal spirit. After the dead person was removed, the hut was swept out, the garbage was thrown away, and thus death was driven out. The surest remedy was jumping over a fire and playing the kantele, a musical instrument. On the way to the cemetery, we stopped at a special memorial tree, tying colored threads around its trunk. Such a tree was a kind of analogue of the World Tree, and the World Tree, as we know, connects all worlds into a single whole and is the road to the afterlife.

Finnish epic and Kalevala

If you ask what the Finnish epic is called, almost everyone will answer - “Kalevala”. It is the most translated book written in Finnish; it was translated and re-sung in sixty languages of the world. And the poem tells (like many epics, “Kalevala” has a poetic form) about the exploits of great heroes, about their rivalry, matchmaking and search for a wonderful source of abundance, for which they had to descend into the underground kingdom and there engage in single combat with the powerful and terrible mistress of the northern lands are the abode of the dead.

Elias Lönnrot, who is called (after Mikael Agricola) “the second father of the Finnish language,” was an outstanding scientist - dictionary compiler, educator, journalist, and folklore collector. He addressed educational publications to the Finnish-speaking peasantry, scientific articles and translations of samples of Finnish folk poetry to the Swedish-speaking intelligentsia.

Elias Lönnrot was a practicing physician who fought epidemics of cholera, dysentery, and typhus; published the very popular book “The House Doctor of the Finnish Peasant” (1839) and the first botanical reference book of Finland (1860). He lived a long life and left a great legacy, but the main contribution he made to world culture was the famous “Kalevala”.

During his vacations, which Dr. Lönnrot took for various periods, he traveled around Finland and Karelia, collecting folk songs. His goal was to unite these disparate runes into a single whole, into a complete, holistic work.

Lönnrot was not the first collector of Finnish folklore: his predecessor is called the historian and ethnographer Henrik Gabriel Portan (1739-1804). Portan argued that "all folk songs come from one source" and therefore can be combined.

Lönnrot wanted to present to the world community a majestic national epic similar to the work of Homer.

He worked on Kalevala for more than twenty years. The beginning of this work can be considered the master's thesis “Väinämöinen - the deity of the ancient Finns” (1827).

Over fifteen years of expeditions, often under difficult conditions, undertaken alone, Lönnrot covered a huge distance on foot, on skis, and by boat. In 1833, “Pervo-Kalevala” (a collection of runes about Väinämöinen) was published. However, he did not publish it, because by that time he had collected even more material. As a result, on February 28, 1835, “Kalevala, or Old Runes of Karelia about the ancient times of the Finnish people” was finally published. The book was published in a circulation of five hundred copies. The text consisted of thirty-two runes.

The significance of this event is difficult to overestimate. February 28 has since been celebrated in Finland as Kalevala Day, a national holiday, a day of Finnish culture.

Soon, in 1840, J.K. Grot translated “Kalevala” into Russian.

And Lennrot continued his work. He inserted blank sheets into his copy of the Kalevala edition and set off on the expedition again. On these sheets he wrote down new runes to complement the old songs. Finally, in 1847, Lönnrot combined all the folk songs he had collected into a single cycle. The poem has a chronological sequence and a unified compositional and plot logic. “I considered that I had the right to arrange the runes in the most convenient order for their combination,” Lennrot wrote.

The New Kalevala was published in 1849 and consisted of fifty runes. This version became canonical.

At the center of the story is the conflict between two worlds - Kalevala (the world of people) and Pohjola (the afterlife). This conflict was invented by Lennrot himself; in mythological systems everything did not happen so clearly. It should also be remembered that Elias Lönnrot worked in the era of romanticism, and this movement in literature and art is characterized by sharp contrasts between high and low (high and low), as well as a great interest in the folk, national.

The images of epic heroes under the pen of Lennrot were transformed: from “dark” mythological figures they turned into “living people”. Lönnrot’s creativity was especially pronounced in the depiction of tragic figures that did not exist at all in folk poetry, for example, in the image of the avenger slave Kullervo or the image of the girl Aino (by the way, both this girl and her name were entirely composed by Lönnrot himself; later the name “Aino” - “the only one” - became popular among Finns and Karelians).

The “fictional” image of Aino, who did not want to become the wife of old Väinämöinen and went to the sea, where she died, nevertheless fully corresponds to the spirit of folk poetry. The author’s descriptions of the heroine’s actions are taken from folk stories; they are not related to the myth of Väinämöinen, but do not contradict folk songs.

One of these songs tells about a girl who broke branches into a broom in the forest. There she was seen by the mysterious creature Osmo - the one who first brewed beer from barley (in some myths a deity, in others a cultural hero). Osmo wooed her, but the girl, when she came home, did not change clothes for the wedding, but committed suicide. Aino did the same in Kalevala.

Thus, the situation with the Finnish epic is truly unique.

On the one hand, “Kalevala” is a story about the epic heroes of Finnish antiquity, something like Russian epics.

On the other hand, this is the work of a specific person, Elias Lönnrot, albeit a scientist, albeit a conscientious collector, researcher of folk art, but still, first and foremost, a poet.

Who is the creator of “Kalevala” - the people or Dr. Lennrot?

For many years, the Kalevala was considered a Finnish epic. This is how it entered world culture, and this is how thousands of people perceive it.

The first Russian translator of the Kalevala, Grot, called it “a large collection of works of folk poetry.” (Elias Lönnrot is only a collector of texts). The German scientist Jacob Grimm published an article “On the Finnish Folk Epic” in 1845, in which he also adhered to this view. The translator into Swedish, Castren, also convinced readers that “in the entire Kalevala there is not a single line composed by Dr. Lönnrot.”

However, in the second half of the nineteenth - early twentieth centuries, scientists, primarily Finnish, established: Lönnrot often combined songs of different genres; in his epic they generally do not appear in the form in which they were performed by rune singers. “Kalevala,” they argued, is an author’s work.

In Russia, the dominant point of view was that Kalevala was a folk epic. It became especially established during Soviet times. The collector of this great folklore work - evidence of the creative power of the people - was named the “modest rural doctor” Lennrot, who simply loved folk songs.

In 1949, the outstanding philologist and folklorist V.Ya. Propp prepared the article “Kalevala in the light of folklore.” This article was written in the form of a report that Propp was going to deliver in Petrozavodsk at a conference dedicated to the centenary of the Finnish epic.

“Modern science cannot take the point of view of identifying the Kalevala and the folk epic... Lennrot did not follow the folk tradition, but broke it, he violated folklore laws and norms and subordinated the folk epic to the literary norms and requirements of his time,” wrote V. Ya .Propp.

Actually, he was right, but his point of view did not fit into the framework of official guidelines at all. The report did not take place. The article was published only in 1976.

Currently, the view of “Kalevala” as “the epic poem of Elias Lönnrot” has finally been established. (Just as the Iliad and Odyssey are Homer's epic poems).

The word “Kalevala” itself means “land of Kalev.” Kaleva is a kind of mythical ancestor, therefore the main characters of the epic are his descendants. Kaleva is known primarily in the folk poetic tradition of Finns, Karelians and Estonians as a character who lived a long time ago. The memory of him remained in the form of various unusual objects (huge stones, cliffs, holes; in the sky it is Sirius - the star of Kaleva, the constellation of Orion - the sword of Kaleva). Lightning is the fires of Kaleva.

The main meaning of the word “kaleva” is “giant”, mighty, seasoned, enormous. “Kalevan kansa” of Lönnrot’s poem is “the people of Kaleva” (this expression has no correspondence in the folk tradition, it is the creation of Lönnrot himself). The land of Kaleva is Kalevala. The name “Kalevala” itself, although not found in the folk poetic tradition (the concept of “country” in folklore is usually conveyed by the concepts of “native side” or “foreign land”) still exists in the language. In wedding songs, Kalevala is called a house or an estate.

One way or another, Kalevala in Lönnrot’s epic is a mythical country where the main events of the poem take place and which is represented by its main characters - Ilmarinen, Lemminkäinen, Kullervo and, first of all, Väinämöinen.

The central character of Kalevala is the old man and sage Väinämöinen. This is a cultural hero, an inhabitant of the primary World Ocean. He participates in the creation of the world along with the demiurge - after all, it was Väinämöinen who created rocks and reefs, dug fishing holes, got fire from the belly of a fiery fish (salmon), and made the first net for fishing. In some myths, Väinämöinen also created the fire fish: this happened when a certain fish swallowed the spark he struck. That's why salmon has red meat. Actually, Väinämöinen had to invent the world’s first fishing net precisely in order to catch the salmon thief and remove the swallowed spark of the primordial fire from his belly.

Some runes say that Väinämöinen produces fire from his hand together with his main ally and rival (sometimes brother) Ilmarinen. They do this in the eighth heaven of the nine-layered vault of heaven.

The idea of multi-layered worlds - especially the upper and lower ones - is associated with shamanic practices of traveling through alien spaces, the abode of gods, spirits, demons, and ancestors. Most often, Finns have a three-layer palate, sometimes seven layers; in the quoted rune it has nine layers.

So, Väinämöinen knocked out a spark, but it slipped from the upper layer of the sky down and through the chimney fell to the ground, into the baby’s cradle, scorching the mother’s chest. Saving her life, the woman wraps the spark into a ball and lowers it into Tuonela - into the river flowing through the kingdom of the dead. The river boils, its waves rise above the fir trees, and then a fish swallows the spark.

On the ground, meanwhile, the flames are raging with might and main, and only behind the “Akhti barn” (in the sea) there is no fire.

A snake swam in the sea, born from the spit of the witch Xuetar. This snake was caught and burned, and the ashes remaining after the procedure were sown on the ground. From the ashes flax grew, from the flax they made threads, from the threads Väinämöinen wove a fishing net and threw it into the sea. So he caught a fiery fish, which carried a spark in its belly. By the way, Väinämöinen had to use copper mittens mined in Pohela, otherwise the fish would have burned him.

In this legend, cultivated, domestic fire is contrasted with the fiery element. A fire raging on the ground is deadly for humans. But the spark obtained by Väinämöinen is a different matter: the cultural hero tame it, domesticate it, put it in a cradle and raise it as if it were a baby.

The “ice maiden of the cold” arrives from the same Pohjola as the “tamer” of the small fire. It reduces the power of fire and keeps it in check. And to treat burns, the deities send people a bee with its healing honey.

Another act of Väinämöinen, a culture hero, was the creation of the first boat. Selecting a tree for construction, he asks the oak tree for consent: does it want to become the skeleton of a future ship? Oak is not against it, but on one condition: Väinämöinen will build a battle boat out of it, and voluntarily lies down in the hero’s sleigh. But Väinämöinen's work stalled: he lacked three magic words to complete the process.

Väinämöinen had to go to the afterlife to get the necessary “tool”. The path there is difficult: you need to walk along the blades of axes and swords, along the points of needles.

There, in the afterlife, a certain giant Vipunen sleeps in a dead sleep. This is an ancient giant of primordial times who remembers a thousand spells. However, the main difficulty is that he died a long time ago, alder grew on his chin, and pine trees sprouted from his teeth. It’s not easy to get a clear consultation from such a creature, but Väinämöinen finds a way out: he sneaks into Vipunen’s womb. But even there he cannot obtain the secret knowledge that the dead giant possesses. Then Väinämöinen builds a forge right in the giant’s womb. In this forge, he forges an iron pole and wounds Vipunen's insides. With his sixth, Väinämöinen bursts open the giant’s mouth and floats through the monster’s veins on a boat for three days.

Such behavior, as they say, would awaken the dead. That's exactly what happened. Experiencing terrible torment, Vipunen finally woke up and, in order to get rid of the culture hero, told him all the necessary knowledge.

Now the main thing is to safely leave the kingdom of the dead, which is vigilantly guarded by guards - the daughters of Tuoni. But Väinämöinen is now filled with ancient wisdom, he turns into a snake and eludes the guards.

But the difficulties when building a battle boat from oak (sometimes, by the way, this is the World Tree, and not just oak) do not end there. While hewing out the boat, Väinämöinen injured his knee because Hiisi turned the ax against the master. To prevent blood from flowing out of the wound, Väinämöinen cursed everything that flows - all waters, all rivers and streams. Then he turned to the iron and reminded him that when it was pulled out of the swamp in the form of ore, it was not at all so great and arrogant as to hurt people.

According to archaic ideas, in order to eliminate a disaster, one should tell about where it came from. Therefore, Väinämöinen spends a lot of time telling the iron the story of its origin. At the same time, he tells the iron that they are relatives: like man, iron is a child of Mother Earth.

Having calmed the ax and stopped the bleeding, Väinämöinen went to look for a healer, but did not find one either in the lower world or in the middle. Only in heaven was an old woman found who healed the wound with the honey of a wonderful bee. (By the way, just after this injury, Väinämöinen swam in the waters of the original World Ocean, sticking out his sore knee, when the demiurge bird, a duck, laid her egg on this knee. In the mythological ideas of the Finns, the idea of Väinämöinen as a kind of primordial being who found himself in the ocean before the creation of the world, and at the same time as a cultural hero. And then he acts as an epic character. And this is the same Väinämöinen!)

Another great deed of Väinämöinen, a culture hero, was the creation of the musical instrument “kantele”.

This is what happened.

As we remember, Väinämöinen’s boat considered itself a warship, but the creator did not use it for any glorious deeds. And the rook loudly complained about this circumstance.

To calm her down, the hero equipped a squad of rowers and sent them out to sea to look for adventure. But the boat got stuck in the ridge of a huge pike.

Rescuing his “brainchild,” Väinämöinen cut the monster with a sword and created a stringed musical instrument from the pike’s spine, which was called the “kantele.” Hiisi's hair was used for the strings.

Kantele plays a large role in the epic and Finnish culture, and various versions are told about its origin. Sometimes the creator of the kantele is the blacksmith Ilmarinen. In any case, this is a magical instrument, and singing to its music has a magical meaning, these are shamanic spells.

That is why Väinämöinen’s rival, young Eukahainen, is not succeeding. His kantele playing does not bring any fun. But when Väinämöinen himself gets down to business, everything around is transformed: animals and birds, the mistress of the forest and the mistress of the water - everyone is enchanted by this music. Without the singing of Väinämöinen, joy leaves the world, cattle stops “being fruitful and multiplying.”

Some legends have an additional, “romantic” clarification: the fact is that on the boat Väinämöinen was chasing the sea maiden Vellamo and he also created a musical instrument in order to lure her out of the water. But the stubborn maiden turned out to be the only creature on earth who remained indifferent to Väinämöinen’s singing and kantele music.

In general, the beautiful Vellamo - the daughter of the sea god Ahti - had reasons not to trust Väinämöinen. Väinämöinen once caught a wonderful salmon fish. He marveled at her beautiful appearance and immediately decided to cook it for himself for lunch. But it is impossible to cut up such prey with anything, so Väinämöinen asked the god Ukko for a golden knife. While the trial is in progress, the salmon turned into the beautiful Vellamo mermaid. She threw herself into the waves and sent a bitter reproach to the fisherman: she wanted not to be eaten, she fell in love with Väinämöinen and was going to marry him, but now it’s all over. After this, Vellamo sailed away, and Väinämöinen searched for her for a long time and in vain. Actually, trying to pull her out of the depths of the sea with a special rake, he created many underwater holes, and at the same time created underwater rocks and shoals...

In another rune, where the creator of the kantele is Ilmarinen, the magical essence of this instrument is even more clearly emphasized. Music is essential for the shamanic journey through all three worlds.

As we remember, the core connecting all three worlds is the World Tree. And then one day the blacksmith Ilmarinen comes to an oak tree, which represents one of the incarnations of the World Tree, and wants to cut it down to make a kantele. But the oak tree is not ready to be cut down: a black snake lies on its roots, a vulture sits in its branches (the upper and lower worlds are unfavorable for humans). It is allowed to begin work only after the picture has changed, and the other worlds have become favorable: a golden cuckoo crows in the branches, a beautiful maiden sleeps at the roots. Now the tree is suitable to become a material for kantele - a conductor to different worlds.

Väinämöinen's playing on the kantele turned out to be so attractive to the creatures of the earthly world that even the Sun and the Moon listened and descended from heaven to the top of the pine tree.

This should not have been done - they were immediately captured by Louhi, the evil mistress of Pohjola. She hid the Moon in a motley stone, and the Sun in a steel rock and sealed them with a spell.

Darkness fell on the world, grain stopped growing, cattle did not breed, even the god Ukko sat in darkness.

Then the people turned to the blacksmith with a request to forge new luminaries. Ilmarinen got down to business and made a month out of silver, and the sun out of gold. He hung these artificial luminaries on the tops of trees - pine and spruce - but there was no point.

People did not know who was to blame for the disappearance of the Sun and the Moon and where they were now hidden. Väinämöinen found this out: the fortune-telling chips of alder wood definitely pointed him to Pohjola. There's nothing you can do - you have to go.

Väinämöinen headed to the gates of Pohjola and near the river that separated the world of the living from the world of the dead, he shouted to the guards of Pohjola to give him a boat. However, they replied that they did not have a free boat. Väinämöinen had to turn into a pike and swim across the stream. On the opposite bank, he fought a battle with the sons of Pohjola (residents of the afterlife).

Finally he reached the island, where the stolen luminaries were hidden under a birch tree in a special rock. With his sword, Väinämöinen drew magical signs on the cloud, after which the rock split, and snakes came out, which the hero killed.

The main thing left was to open the locks, and Väinämöinen had neither the keys nor the suitable spells. So he turned to the blacksmith Ilmarinen and asked him to forge master keys.

While the blacksmith was hammering, the old woman Louhi suspected something was wrong and flew in the guise of a hawk to see what Ilmarinen was doing so interestingly. He told the hawk that he was forging a collar for Loukha - he wanted to chain her to the foot of the rock. The mistress of Pohjola was so frightened that, of her own free will, she returned the Sun and Moon to the people.

The cosmogonic myths of other Finno-Ugric peoples allow us to give this legend a slightly different interpretation. In a number of cases, the mistress of the underworld acts not as a thief of the luminaries, but as their first owner. After all, the Sun and Moon originally were at the bottom of the World Ocean, in the underground world, where the wonderful egg fell. From there the luminaries are obtained by a magic bird and a hero-blacksmith.

It is interesting to note that Ilmarinen is unable to forge a new sun and moon. Why? After all, the blacksmith participates in the creation of the world; he was once a “forger of the heavens”!

The fact is that by the moment described in the rune about the return of the Sun and Moon from Pohjola, the era of creation was over. The hero can no longer create anything new, he can only work on developing the well-being of humanity, creating cultural benefits - like a boat, a net, an ax, and so on; but no one can create light again.

Another thing that Väinämöinen takes from Pohjola (having lulled the guards to sleep by playing the kantele) is a wonderful sampo mill.

The embodiment of a people's dream

Sampo is a source of abundance, a magical object with a broad basis in folk tradition. The image of the miracle mill is the embodiment of the people's dream of prosperity and a comfortable life.

It is interesting to note that Elias Lönnrot, describing sampo in his “Kalevala,” does not rely on the most common version of the story about sampo, but, on the contrary, on a single one. A single four-line description of a sampo mill - a triune self-grinder, which has a flour grinder on one side, a salt grinder on the other, and a money grinder on the third - was brought from Russian Karelia in 1847, and the collector of folklore - this time not Lönnrot himself, but D.Evropeus - did not even indicate from whom he received the poetic excerpt.